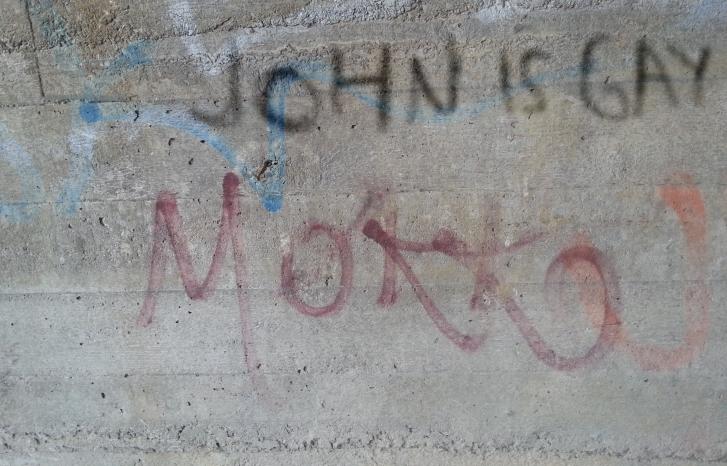

On the internet, in the workplace, on the bus and in the neighbourhood. LGBT people are victims of hate speech much more frequently than the rest of the population. Whereas ten per cent of the majority population say that they have been exposed to comments that they consider hateful over the past year, twenty-three per cent of the LGBT people – more than twice as many – give the same answer.

This is shown in a new report published by Institute for Social Research (ISF). The report describes LGBT people’s experiences with disparaging comments, hate speech and outright threats.

Most of those who have experienced threats have been targeted several times.

“The term ’hate speech’ refers to comments that are meant to create or spread hatred towards certain groups in society,” says researcher Audun Fladmoe, who has co-authored the report with Marjan Nadim.

“We have used two criteria as points of departure: One is the tone, which has to be discriminating, harassing, threatening or hateful. The other is the basis for the comment, that is whom it is directed towards,” he says.

Experience threats

The Norwegian criminal code protects people against discriminating and hateful comments performed in public based on ethnic origin, religion, sexual orientation or functional ability.

The report shows that LGBT people are victims of this type of speech to a much higher extent than the rest of the population. If we also include commentaries directed at gender identity and gender expressions, the difference between LGBT people and the rest of the population further increases.

The difference is particularly big when it comes to concrete threats. Fifteen per cent of the LGBT people say that they have been exposed to threats, whereas the same applies to four per cent of the general population.

“Although this is a minority, I still think that fifteen per cent is high,” says Fladmoe.

“Most of those who have experienced threats have been targeted several times.”

Fladmoe explains that the figures are more or less the same when it comes to comments such as ‘you shouldn’t have been born’ or ‘you don’t have the right to live’: Sixteen per cent of the LGBT people and three per cent of the general population have experienced comments like this.

“It thus seems like approximately fifteen per cent of the LGBT population have experienced the worst comments. If you look at the two numbers together it is quite serious,” he says.

Hatred behind the keyboard

According to the report, most of those who are victims of hate speech are targeted online, such as Facebook and Instagram, in comments sections and other online fora. The report also shows that those who are the most active on the internet are also the most exposed.

“We have found that those who are politically active, participate in online debates and comment sections, are more likely to receive hate speech than those who don’t participate online to the same extent.”

“Young people receive more comments than older people, is that because they are more active online?”

“Yes, partly, but even when we take online behaviour into consideration, the younger generations are still the most exposed,” he says.

Those with one minority characteristic are more exposed than the general population.

According to the criminal code, a statement is public if it can be seen by twenty to thirty people online. In light of this, a Facebook status or a comment on an online article is normally counted as public. According to Fladmoe, hate speech can make a major impression.

“If you observe a comment directed towards a group that you belong to yourself, this statement can create fear even though the comment may not be addressed to you directly. We see that many LGBT people feel unsafe by just observing the comments, not by receiving them directly, whereas the rest of the population do not. Feeling unsafe is a fairly strong reaction,” he says.

Double discrimination

According to the report, people who belong to more than one minority, who are both queer and have minority background for instance, are far more exposed to hate speech than people with only one minority characteristic. This particularly applies to comments directed towards characteristics that are protected by the criminal code in addition to gender expressions.

“We have asked about affiliation to many minority groups, and we see that those with one minority characteristic are more exposed than the general population,” says Fladmoe.

“The likelihood of being targeted increases even more among those with two or more minority characteristics. These people experience pressure from many sides. This is also confirmed by previous studies,” says Fladmoe.

For example, he refers to a report about living conditions among queers with minority background in Norway published by Nordland Research Institute last year.

This report, which contains results from a survey and qualitative interviews, has found a high occurrence of negative comments based on sexual orientation or gender identity among the participants.

“Our results mirror each other, and we are beginning to get a fairly clear picture,” says researcher Helga Eggebø, who has written the report.

It shows that a significant minority of the participants say that they perceive communities with the same ethnic background as themselves as exclusive towards queers.

“This particularly applies to those with background from countries where the majority of the population are Muslims,” says Eggebø.

“Fladmoe and Nadim’s report points in the same direction, since they have found that people from a different religious background than the Christian or secular experience more negative comments.”

Most have good living conditions

The report also shows that several people experience being excluded from queer communities, significantly more people than those who experience being excluded from their work environment or student environment.

“Some said that they felt excluded from queer communities because of their immigrant background. For instance, they had experienced being exposed to sexual stereotypes or disparaging comments on dating fora, or racism and exclusion in queer organisations,” says Eggebø.

“Those who feel excluded from ethnic minority communities due to negative attitudes to queers may become particularly vulnerable to social marginalisation. This is quite serious, and it thus becomes even more important that these experiences are documented.”

According to Eggebø, it is also important to emphasise that many of those who were interviewed described strong affiliation and support. This applied to both ethnic minority groups and queer communities, and such communities were important for how the participants handled discrimination and hatred.

She also emphasises that queers today primarily report about good living conditions.

“According to the survey ‘Sexual orientation and living conditions’ (Seksuell orientering og levekår) from 2013, nine out of ten participants are not exposed to discrimination in the workplace,” she explains.

Only a small minority has experienced violence, and the amount of suicide attempts have been highly reduced since the 1990s.

Over a relatively short period, queer people have fought for and obtained a number of important, formal rights such as civil partnership, the Marriage Act, access to assisted insemination for lesbian couples and the Anti-Discrimination Act for gender identity.

“At the same time, those of us who live queer lives experience more types of discrimination and exclusion based on sexual orientation and gender,” says Eggebø, who has addressed this problem in the op-ed ‘A Queer Fairy tale?’ (‘Et homoeventyr?’).

“For instance, homosexual boys report a six times higher occurrence of bullying than heterosexual boys. It is important to document these experiences of discrimination in order to be able to confirm the victims’ experiences, and because they make up an important foundation for developing good and relevant political measures.”

Creates fear and mobilises

People who are victims of hate speech often react by getting upset or angry, according to ISF’s report. It also shows that LGBT people to a higher extent than the rest of the population feel unsafe, but it varies what consequences the hate speech has for the affected person.

The report divides the consequences into three categories: Emotional reactions, mobilising reactions and withdrawal.

Most people do not file a report, and many reports are dismissed.

“We see that LGBT people react stronger than the majority population in all categories. More of them withdraw and become less active in debates, but there are also more who become angry and mobilise. Hate speech has different consequences for different people,” says Fladmoe.

Some withdraw, delete their profiles at various online fora, block people and keep away from comment sections, and for some it also means that they become afraid of being out in public because they have received threats. Fladmoe further explains that it is a problem for the public debate if certain groups are underrepresented because they do not dare to speak up for fear of being harassed.

“We know that this often happens with young politicians, for example. It is a general problem, but it becomes particularly serious if the harassment is distributed unequally as well. If certain groups are harassed more than others, these groups also end up being underrepresented, which makes the problem even bigger,” he says.

Will strengthen the protection against discrimination

What can be done in order to combat hate speech? Some people report experiences with hate speech to the police, but only the most severe instances are covered by the criminal code, and the threshold is high. There is also reason to believe that the number of unrecorded cases is high, says Helga Eggebø.

“Most people do not file a report, and many reports are dismissed. It is a way of placing responsibility, but it is a strategy with limitations,” she says.

Besides, the criminal code does not protect against hate speech directed at gender expressions and gender identity, only against sexual orientation.

“You may look at it as a lacuna in the legal system. Seeing how many people who are exposed to hate speech on this basis, perhaps the law should be expanded.”

Nevertheless, Eggebø has more faith in strengthening the protection against discrimination, the civil legal area covered by the Equality and Anti-Discrimination Act, which forbids harassment and other infringements. According to her, the low-threshold service is particularly important.

“You may lodge a complaint to the Equality and Anti-Discrimination Tribunal if you are exposed to discrimination. You can also contact the Equality and Anti-Discrimination Ombud for advice,” she says.

“A good low-threshold service that is perceived as accessible and offers effective opportunities for sanctions is decisive for legal protection. Strengthening the protection against discrimination is an important measure, and something politicians have both the power and the opportunity to implement.”

Same contents, other words

Eggebø regards the report from ISF as an important contribution to research on living conditions and experiences with discrimination among LGBT people. At the same time, she sees a need for a review of all the already available research in the field.

In a previous collaborative project with Nadim and Fladmoe, Eggebø and researcher Elisabeth Stubberud gathered empirical research on negative comments, harassment and hate crime directed at LGBT people.

Hate speech is in reality a type of negative comment.

“If you conduct a literature search on hate speech, you will get a lot of philosophical and juridical reflections related to freedom of speech and democratic values. Yet until a couple of years ago, there have been few empirical studies of hate speech,” she says.

“What we did in the report was to zoom out and ask ‘what are we really talking about here?’ Hate speech is in reality a type of negative comment. It is more specific and more serious, but it is nevertheless the same as negative comments directed at minority groups, and there is a certain amount of research on that.”

She points out a survey on living conditions for LGBT people from 2013 in which all participants were asked whether they had experienced negative comments based on sexual orientation in the workplace or at their place of study. The survey finds that a significant share of the participants had such experiences, but it was not characterised as hate speech.

“The same applies to research on children and youth, where hate speech makes up a part of a discourse on bullying. Thus in practice we are talking about much the same, but we use different words. I think we need to connect research on hate speech directed at LGBT people to the existing research on living conditions in order to take the discipline a step further,” says Eggebø.

Translated by Cathinka Dahl-Hambro.

- The report ‘Experiences with hate speech and harassment among LGBT people, other minority groups and the general population’ (‘Erfaringer med hatytringer og hets blant LHBT-personer, andre minoritetsgrupper og den øvrige befolkningen’) was published by Institute for Social Research (ISF) 11 February this year. The report is written by researchers Audun Fladmoe and Marjan Nadim.

- The report consists of results from two surveys. One has been conducted among LGBT people and the general population, whereas the other has been conducted among members of FRI – National Association for Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals and Transgender People, Jewish organisations and Sami organisations.

- It shows that almost one of every four LGBT people have been victims of what they experience as hate speech over the past year.