"The AIDS epidemic changed Norwegian society a lot more than people realise," says Ketil Slagstad, historian and postdoctoral fellow at Charité Berlin – University Medicin,.

His newly released book is titled Det ligger i blodet. Epidemien som forandret Norge (It’s in the Blood. The epidemic that changed Norway) (2023).

When the AIDS epidemic hit in the mid-1980s, it created an upheaval in most people’s everyday lives.

"But today, many aspects of the history of AIDS have been forgotten," says Slagstad.

Confusion in the 1980s

It was a mysterious disease.

"In the mid-eighties, we didn't know for sure how people became infected with AIDS.”

"People thought you could catch AIDS by French kissing, being in a swimming pool or by sitting on a public toilet.”

Was it safe to shake hands or kiss your child goodnight? The research provided no definitive answers.

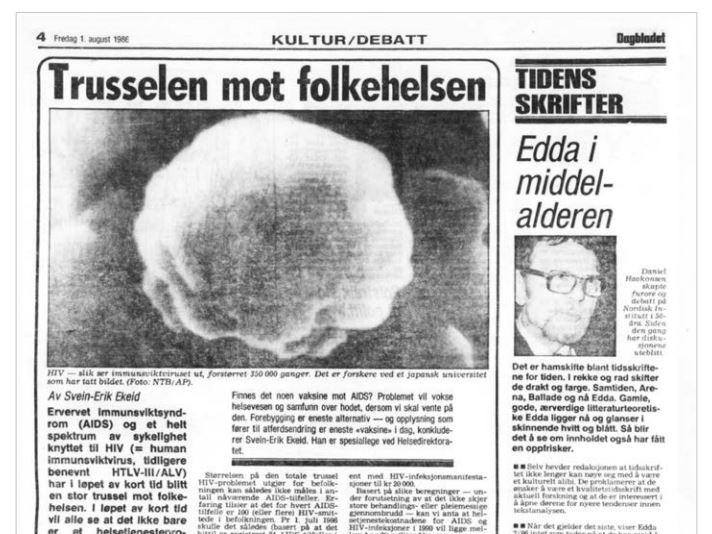

One group of researchers believed that the disease could be transmitted via mosquito bites, as reported by the newspaper Dagbladet in 1985:

"If that’s the case, humanity faces an unimaginable catastrophe."

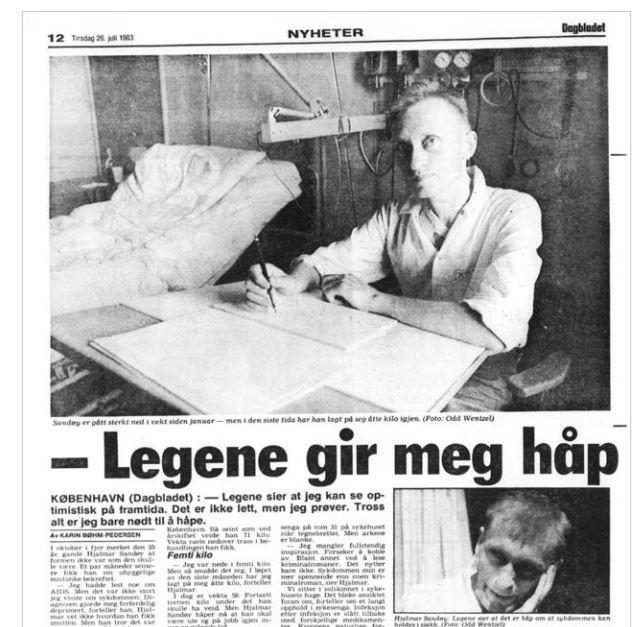

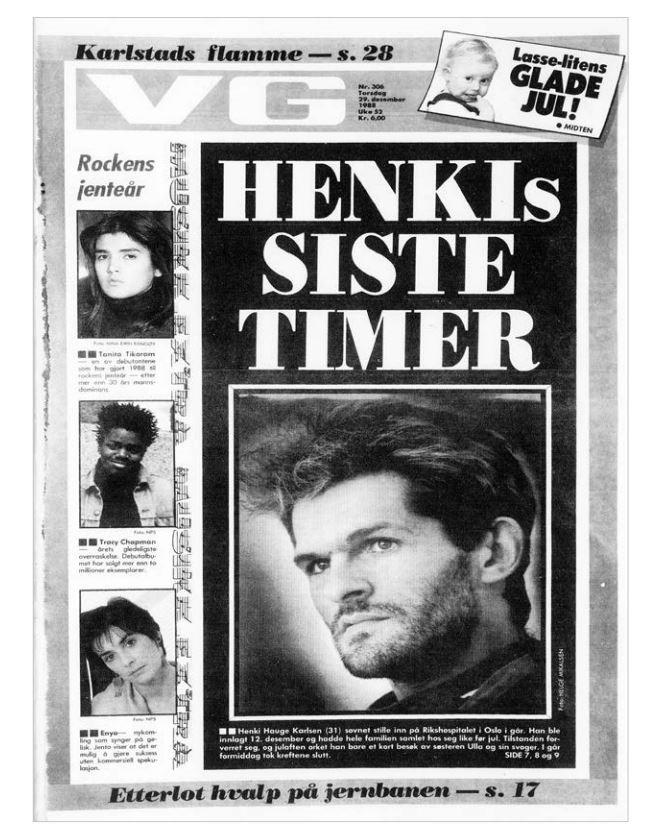

The first hospital admission

The first hospital admission in Norway happened a couple of years earlier, on 19 January 1983.

The man was 30 years old and was admitted to Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet with a fungal infection in his throat.

"That is extremely rare in an otherwise healthy thirty-year-old, and his condition quickly deteriorated," says Slagstad.

The patient had a high temperature, suffered from diarrhoea for more than three months, and lost weight.

When a herpes virus attacked his eyes, the patient went blind.

"He also developed an unusual skin cancer, Kaposi's sarcoma, which manifests itself as blue-violet lesions on the skin.”

Slagstad explains that about one in four AIDS patients developed this symptom, and that it sometimes developed into severe ulceration.

In the book, he describes the horrific scenes from the hospital:

"The festering sores confined people to their beds. Even the slightest movement caused the wounds to rub against the lower abdomen, making it impossible to sit or walk."

"Others lost their sense of balance or developed neurocognitive disorders when the virus attacked their brains.”

“There was no treatment,” says Slagstad.

“The doctors were perplexed.”

The “gay plague”?

By 1983, the disease was old news in the United States, but remained much of an enigma.

The term "gay plague" had been used in the American press since the early 1980s, and the disease later became known as GRID – gay-related immune deficiency.

In the early 1980s, the origin of the disease was unknown.

"A number of theories and speculations emerged; it could be a new virus, a new microorganism, or a gay lifestyle disease linked to partying, lots of sex and using drugs such as poppers."

Media hysteria around AIDS

While panic spread in the gay communities in the United States and the death toll rose, the Norwegian media remained surprisingly silent about the epidemic, says Slagstad.

This would change in the mid-1980s:

"At that point, antibody tests became available, making it possible to detect infection in people that appeared healthy. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health made certain forecasts that were published in newspapers. They generated a lot of fear.”

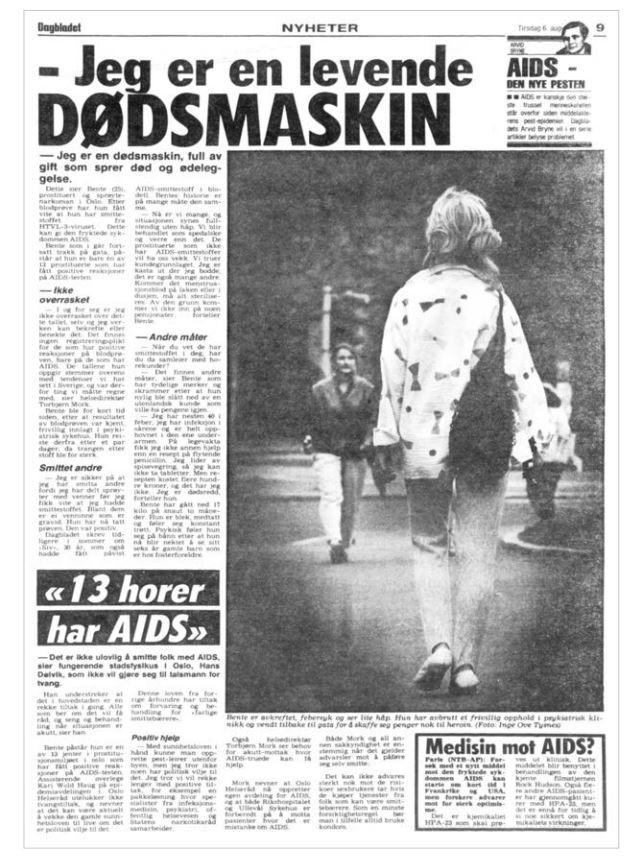

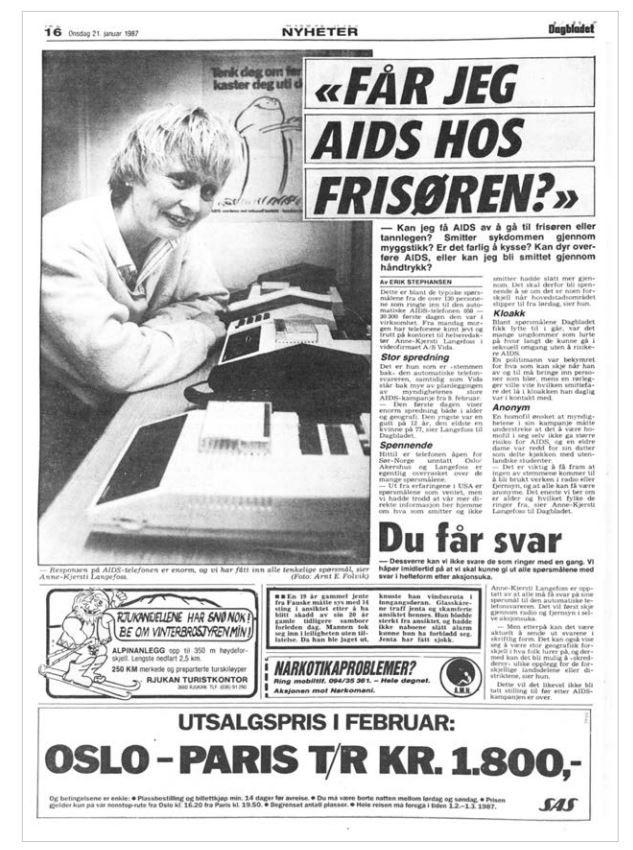

The media whipped up negative sentiments with sensationalist headlines.

"140 prisoners to be AIDS tested", wrote Dagbladet on 3 August 1985.

"Bought sex from AIDS whore", wrote the newspaper VG on 20 May 1988.

"Throughout the history of the epidemic, it was often vulnerable groups that were blamed: sex workers, foreigners, Jews, Muslims and homosexuals," says Slagstad.

As he writes in the book:

"Epidemics breed fear and create stigma."

"It was the health authorities that financed the initiatives."

The double face of stigmatisation

According to Slagstad, stigmatisation had a "double face":

"On the one hand, AIDS increased stigmatisation, particularly of gay men. They were often associated with the disease and their bodies were seen as potential sources of infection.”

"On the other hand, the epidemic forced gay communities into the public sphere, to show their ability to take responsibility for the affected in the community.”

Slagstad explains that the gay community became an active hub for prevention initiatives.

"That generated trust because the initiatives were coming from the activists themselves, not as directives from those outside the community.”

The state was part of administering the initiatives:

"The health authorities financed the initiatives and coordinated the work on prevention.”

The introduction of 'user involvement'

The cooperation between gay activists and the state had major consequences. Particularly in one regard.

"It was crucial to the introduction of 'user involvement'," Slagstad explains.

Nowadays, this goes without saying:

"You can neither implement research nor health policy initiatives without including and talking to those affected, because we’ve realised that the basis of knowledge is dependent on those who are affected by the policy or research.”

"The epidemic introduced this way of thinking into the public administration and research.”

Hollywoodisation of AIDS

The history of the AIDS epidemic in Norway, in which gay activists collaborated with the authorities, differs from other Western countries.

"In countries such as the United States and to some extent the UK, AIDS activism was largely about mobilising in the absence of governmental organisations.”

This story, in which gay communities were ignored and neglected treated, has been portrayed in numerous Hollywood productions and TV shows, including "Normal Heart" (2014) and "It's A Sin" (2021).

Have British and American films and TV series influenced our understanding of the history of AIDS in Norway?

"Yes, I think so," says Slagstad.

"In the 1970s and 1980s, there was a huge mobilisation in many different communities in Norway. This didn't just come sailing across the Atlantic, there was a lot of drive and creativity. The better we understand our own history, the better we understand Norway today.”

“A public health issue”

Why were the Norwegian authorities more involved than authorities in other countries?

"In England, AIDS became more politicised, especially under the Thatcher government. In Norway, we had a wave of neoliberalism, with the Prime Minister Kåre Willoch leading a Conservative government, but the health policy institutions were much stronger in Norway.”

"The epidemic was therefore treated as more of a public health issue," he says.

“In Norway, it was the Director of the Norwegian Directorate for Health who spoke in the media, not the Minister of Health or the Prime Minister,” he adds.

Scandinavian differences

Peter Edelberg is an historian at the University of Copenhagen. From 2019 to 2023 he was part of the research project on Scandinavian LGBT history: "A Nordic Queer Revolution? Homo- and Trans-Activism in Denmark, Norway and Sweden 1948-2018".

He affirms Slagstad's observation:

"The rise of AIDS and how it was handled by different countries varies considerably.”

Scandinavia included.

"In Sweden, strict coercive measures were introduced, including the possibility of detaining those infected with HIV or AIDS against their will and without trial. Tracing infection was compulsory and those infected had to declare their sexual partners. Sweden also closed gay saunas and sex clubs,” Edelberg explains.

With the response of the AIDS epidemic fresh in their minds, Swedish authorities chose a more liberal approach to the COVID pandemic.

In Denmark, however, such strict measures were never introduced.

"Instead, the government worked with gay activists to ensure the best information for groups at risk," Edelberg says.

He calls Sweden's handling of the epidemic a "top-down" approach:

"The government wouldn’t listen to the Swedish activists but, on the positive side, the state provided financial support.”

Why did they respond differently?

Why did the Danish and Swedish authorities respond so differently?

"This has been investigated by Signild Vallgårda, a Danish researcher and professor emerita of public health science. She believes that in Denmark, HIV and AIDS were treated as a minority issue. It was a true collaboration, with Danish authorities listening to and trusting the minority groups.”

"In contrast, Sweden treated it in a similar way to how they once dealt with drug addicts – as individuals who didn’t have the ability to take care of themselves.”

Influenced Sweden’s Covid response

“The strict handling of the epidemic was like a stain on Swedish history," says Edelberg. He believes that the experience of the AIDS crisis played a central role in Sweden's exceptionally liberal response to the COVID pandemic:

"With the response to the AIDS epidemic fresh in mind, Swedish authorities chose a more liberal approach to the pandemic. In contrast, Denmark, despite its previous liberal approach to HIV, chose a more restrictive response to the pandemic,” Edelberg explains.

In general, however, he believes that there is a tendency to let experts take charge in Sweden, while there is a greater belief in Denmark that the people should have a stronger voice.

Safe-sex campaigns

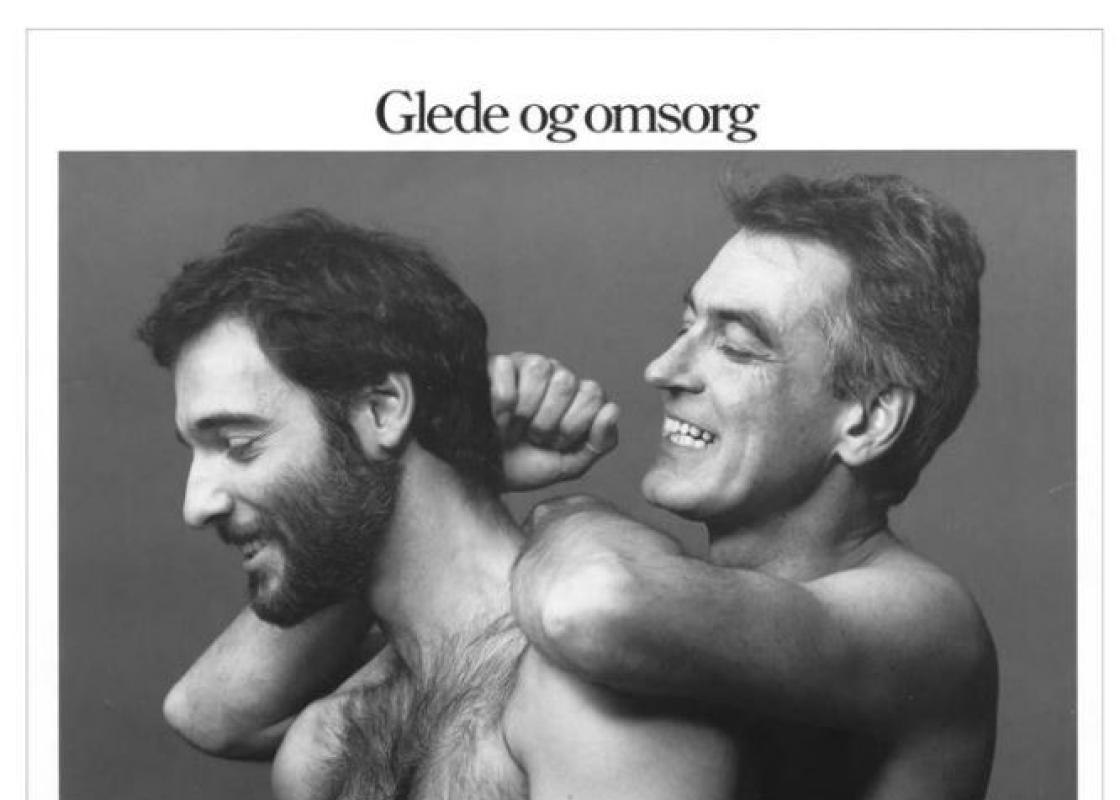

In Norway, the Directorate of Health helped fund a number of campaigns to prevent AIDS, directed by gay activists.

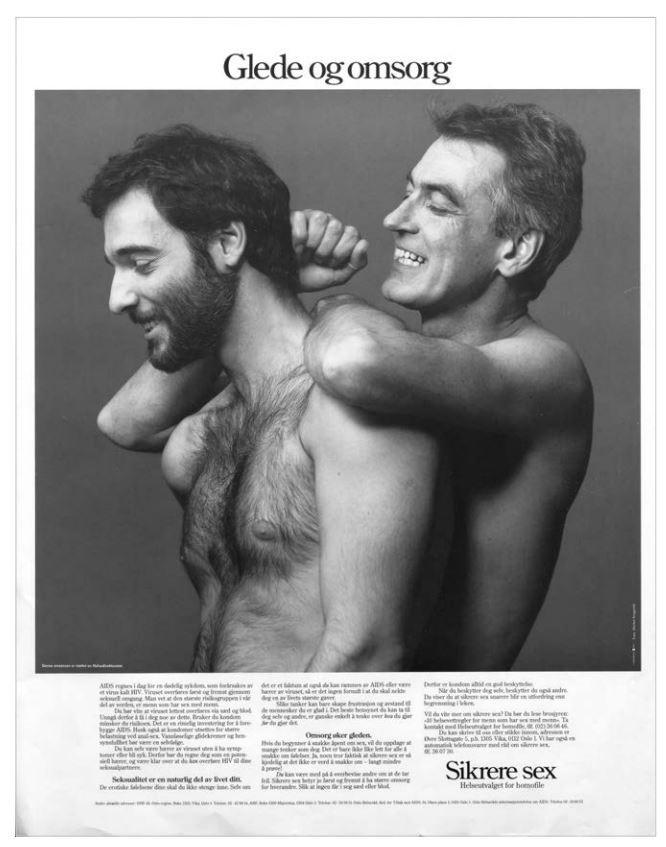

The campaigns were published in national newspapers and made gay identity more visible.

They underwent an interesting development during the course of the epidemic and testify to the fact that openness around sex gradually increased.

"The first campaigns in the 1980s included a lot of text and information. There were headlines such as 'safety and responsibility' and 'pleasure and care', with the goal of destigmatising and strengthening gay identity," says Ketil Slagstad.

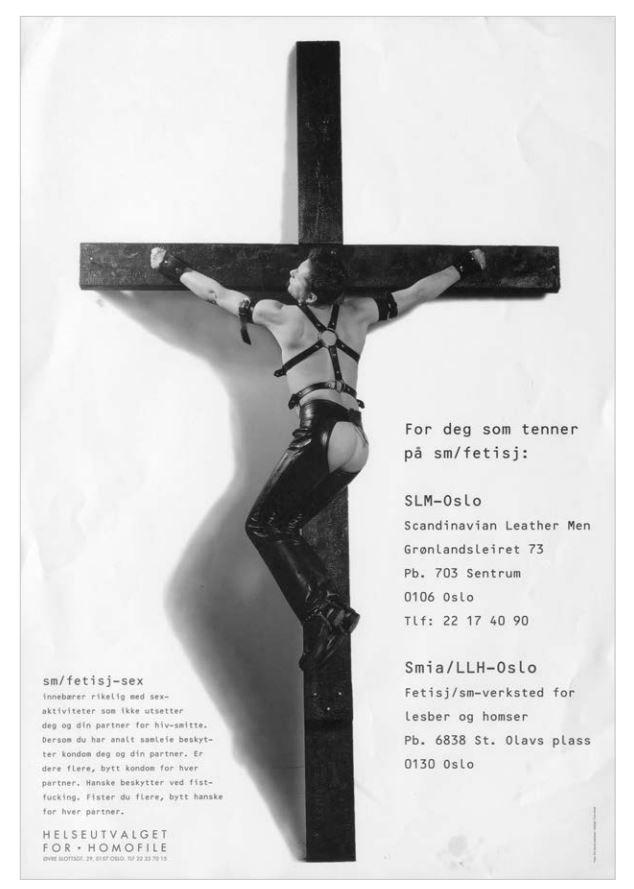

"An interesting observation from the campaigns of the 1990s is how they promoted fetish sex as a safe alternative to traditional sex. Many sexual practices in the BDSM community did not involve the exchange of bodily fluids, so there was no risk of HIV transmission.”

During the 1990s, the campaigns became bolder:

"There were artistic images of erect penises, a man from the BDSM community hanging on a cross and showing his bare behind.”

The language also became more technical:

"Use a condom" and "gloves protect when fisting".

He explains that fisting means having sex by inserting a hand into the rectum.

"An interesting observation from the campaigns of the 1990s is how they promoted fetish sex as a safe alternative to traditional sex. Many sexual practices in the BDSM community did not involve the exchange of bodily fluids, so there was no risk of HIV transmission.”

"It's kind of funny that it was Gay and Lesbian Health Norway that funded the campaigns. That speaks volumes about how far people were willing to go to prevent the spread of AIDS," says Slagstad.

Love talk

Slagstad believes that AIDS contributed to a whole new language of sexuality.

"Both among the broader public and in the gay community.”

The AIDS epidemic made people understand the difference between sexual practices and sexual orientation.

It gave rise to the term "men who have sex with men" (MSM):

"It gradually became apparent that men who had sex with men, but did not identify as bisexual or gay, were a particularly vulnerable group.”

"They didn’t participate in information meetings or read gay magazines, so they were more susceptible to infection," he explains.

“One had to be able to distinguish different groups in order to reach out to them," he explains.

"Not just about gays”

Other groups at risk included drug addicts, sex workers and haemophiliacs ('bleeders').

The epidemic did not only affect homosexuals.

"While gay people had strong advocates fighting their cause, drug addicts and sex workers struggled to be heard in public forums," he says.

It was easier for initiatives from the gay community to gain support among the authorities and in the public sphere.

"It was far more acceptable to support initiatives relating to gay liberation than taking measures for drug addicts and sex workers,” he continues.

Slagstad believes this is partly down to Norway's strict and moralistic attitude towards drugs and prostitution, an attitude that has had cross-party support.

"The consensus that drugs and prostitution are first and foremost an evil that should be prevented through prohibition and social initiatives, hindered an approach that would prevent the spread of the disease," he explains.

Such as strategies to minimise the risks and harm associated with activities such as sex work and substance abuse, by protecting individuals without necessarily changing their lifestyles.

"In the media, drug addicts and sex workers were often portrayed as threats, while their health and well-being were overlooked,” Slagstad concludes.