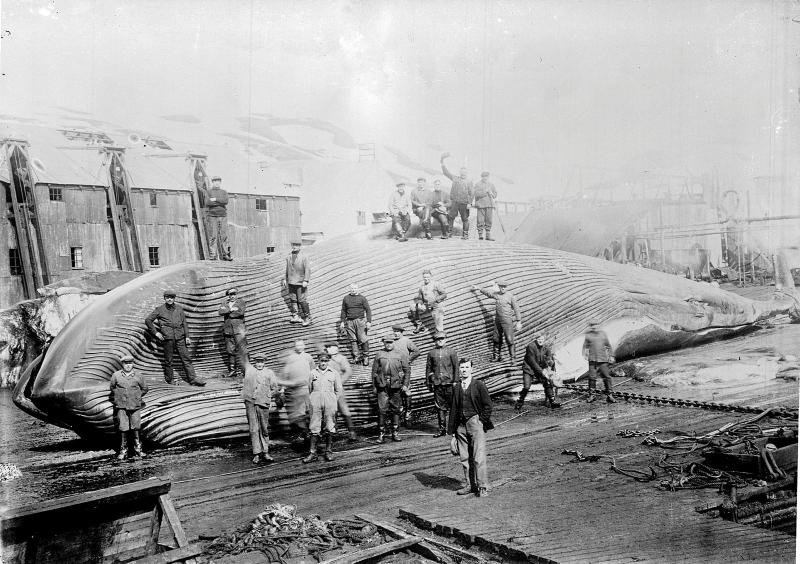

"If you kill a cow, you can hang it in a slaughterhouse and transport it from a dirty to a clean environment. You can't do that with a whale," says the historian and professor of media studies Espen Ytreberg.

In the book Utryddelsen he tells the history of Norwegian industrial whaling.

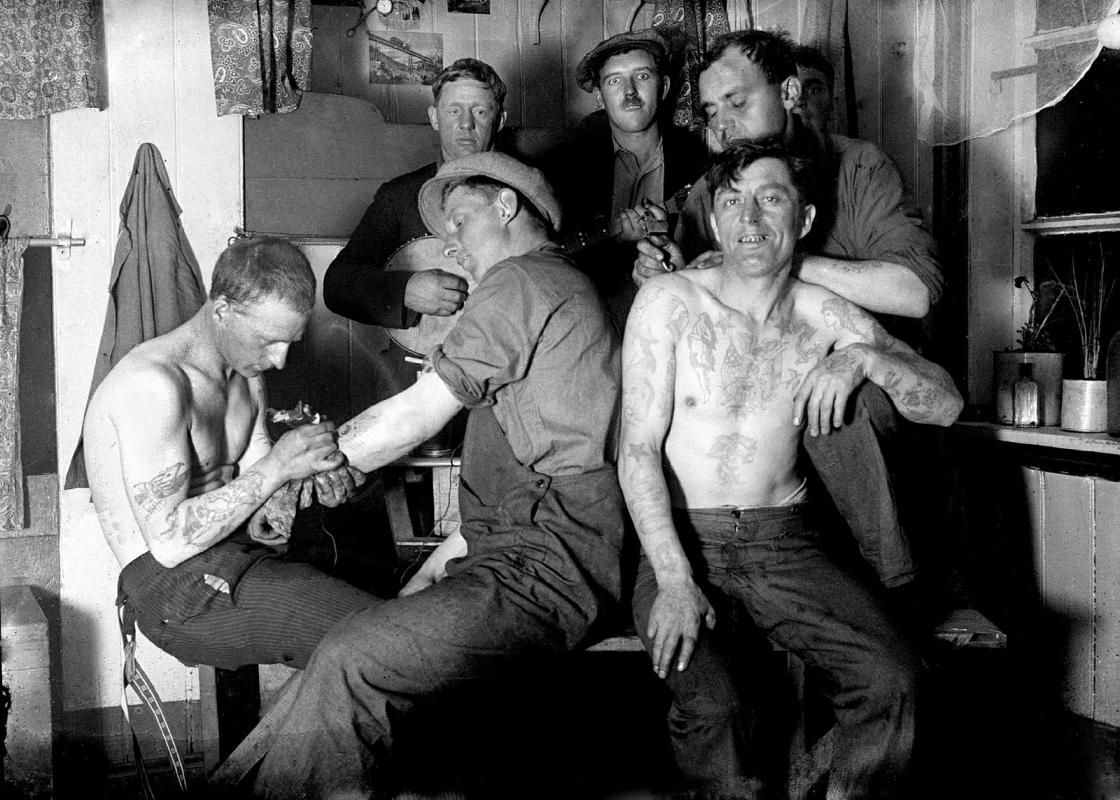

The book includes photographs and autobiographical accounts from whalers and others who worked in the industry.

Ytreberg describes a life of untold toil, blood and gore, and camaraderie in an environment almost devoid of women

The Norwegian whaling industry

The industry had small beginnings along the coast of Finnmark:

"Industrial whaling started in the 1860s. In the early 20th century, the industry rapidly expanded, first into the Antarctic Ocean and then into international waters," Ytreberg explains.

There was a lot happening around South Georgia Island and Deception Island.

"The latter is an island right next to Antarctica, as far away from Norway as you can get. These waters are extremely treacherous," says Ytreberg.

It was here that whale blubber was refined in a processing vessel, ready to be turned into margarine, soap and nitroglycerine.

Norway was at the forefront of whaling nations, with its technical know-how and "exploding harpoons", says Ytreberg.

"However, as a result of the industrial whaling, the number of whales began to decline sharply around the 1960s, and an international ban on whaling had to be introduced.”

In 1962 an international ban on catching blue whales was introduced, and in 1982, a full moratorium was put in place.

Slipping on blood-covered floors

Ytreberg describes the harsh working conditions at the land stations and the swaying flensing plans at sea, where they cut up the whales.

There was blood and gore everywhere:

"When you cut a hole in a whale and dismember it, it releases an enormous amount of matter. It spurts and runs out – lymph, flesh and of course there’s the stench, an intensely vile smell," says Ytreberg.

"The floors were slippery and glistening with fat, water and blood," he writes in the book.

"And this is where the workers would balance, holding their long knives, sometimes using lines to stay upright," says Ytreberg.

Young farm boys from Vestfold, Agderfylkene and Østfold took a job on the ships to earn a living and to see the world," he says.

Many were proud and skilled men:

"The flensers were those who pulled off the outer layer of blubber. Those who dismembered the whale were known as lemmers.”

In the book, Ytreberg describes how the lemmers worked:

"They worked their way into the animal, disappearing halfway behind chopped-up, frayed mounds of flesh [...] Some workers carried a bag on their stomachs filled with sawdust. They dipped their hands into the sawdust to dry off the oil and grease to get a better grip on their utensils."

Two-dimensional "women"

Flensing plans and processing vessels were no place for women, but a few women could be found at land stations: the wives and daughters of senior officials and leaders in the industry.

However, women were present in other forms:

"I'm particularly interested in the world of media, which is why I'm interested in the décor in the workers’ quarters. It was common to have pictures of women, some of which would nowadays be described as softcore pornography. There would also be portraits and pin-ups of movie stars," says Ytreberg.

As the 1900s progressed, it became increasingly common for people to own cameras.

"Some of the men therefore had photographs of their family members, but it wasn't common to display these on the wall. It was more common to a small picture in your wallet or in a drawer.”

Then there were gramophones, the radio and films.

"The sound of women's voices and singing would resonate through these media."

Slept snugly together

Ytreberg explains that buying sex has long been an established part of the international seafaring environment.

"There were brothels in many of the larger ports that the whalers visited: Rotterdam, Cardiff, Curaçao, Buenos Aires, Montevideo.”

"On the processing vessels and at the whaling stations, however, there were no women to be seen, except for the foreman's wife, who you might perhaps see on her Sunday walk.”

Beyond that, there was very limited access to heterosexual intimacy.

However, the whalers were never alone.

The men stood on top of a chest when getting dressed.

"Each man worked as part of a crew and would spent his free time and nights in shared quarters and cabins," says Ytreberg.

One of his sources tells of a ship in 1927 on which up to twelve men were living in just four-square metres.

It meant having to adapt:

"In 1914, , there was so little floor space in the cabins on one of the processing vessels that the men stood on top of a chest when getting dressed.”

"In the book, you write about masturbation?”

“The sources say little about masturbation – it's too taboo. However, one source, a doctor, went around asking in Leith Harbour, a whaling station on South Georgia Island. He managed to squeeze an answer out of the management there, who believed it to be "extremely common".

Total institutions

Wojtek Jezierski is an associate professor of history at the University of Gothenburg and is affiliated with the University of Oslo through a research project on elites in the Middle Ages. In 2010, he defended his doctoral dissertation on monasteries in the Middle Ages: "Total St Gall: Medieval Monastery as a Disciplinary Institution".

Just like Espen Ytreberg, he uses the term "total institution" (defined by the sociologist Erving Goffman) to describe the monks' way of life.

"A total institution is a place that functions as both a workplace and a place to live, where a large number of people live together for a given period," says Wojtek Jezierski.

It's a closed environment.

"All aspects of life, including sleep, leisure and work, are carried out in the same place and in the presence of others," Jezierski explains.

This builds camaraderie, and also creates strong control mechanisms for keeping those living there in check.

Brotherhoods in the Middle Ages

Jezierski explains that the majority of total institutions throughout history have been homosocial, i.e. places where men and women were separated.

Monasteries in the Middle Ages are one such example. Other examples include the military, prisons and old psychiatric hospitals.

“Those living in total institutions had little contact with the outside world. They depended on people of the same sex to meet all of their needs," says Jezierski.

"I'm not talking about physical or sexual needs – although that was also important – but emotional needs. Emotional support, and the experience of sharing the same challenges, such as feeling homesick.”

They referred to each other as "brothers”.

“For monks in the Middle Ages, friendship was incredibly important,” Jezierski explains.

It was just as important to the Knights Templar:

"They referred to each other as 'brothers' and were almost like family.”

Monasteries – a bit like a whaling ship?

"Is it possible to compare a whaling ship in the early 1900s to a monastery?"

"I don't know enough about life on whaling ships, but I imagine there are possible similarities," Jezierski says.

He highlights the feeling of physical vulnerability:

"On whaling ships, the men no doubt felt vulnerable to nature and animals.”

"Although nature also played a role in monasteries in the Middle Ages, there were other, more important factors. Above all, the men would have felt they were surrounded by pagans or false Christians.”

The monks and whalers also had vastly different motivations for isolating themselves. The duration of the time spent together would also be different:

"It’s worth remembering that, according to the Rule of St. Benedict, an aspiring monk should cut all ties with his family and former life.”

“Other members of the monastery were not only the monks’ primary social context, but often their only social context – for the rest of their lives,” Jezierski explains.

“That wasn’t the case for whalers.”

“Oil platforms would probably make a more suitable comparison,” he concludes.

Dressed up

The whalers that Espen Ytreberg describes in his book lived together for varying periods of time.

“So, what about homosexuality?”

"It's not possible for me to say anything about the scale of homosexuality. There are a few references to what one might call brutal prejudice. One whaler who was asked about homosexuality replied: ‘If such a thing was discovered, those in question would probably have been in danger of being thrown overboard’," says Ytreberg.

“That said, other sources show that gender roles may in practice have been more flexible than these prejudices suggest," Ytreberg explains.

When sailing across the equator, they would create a dramatic spectacle.

"In certain situations, there was room to challenge traditional gender roles and to have a more playful and exploratory relationship with both masculinity and femininity, especially when it came to festivities.”

Ytreberg points to a popular initiation ritual:

"When sailing across the equator, they would create a dramatic spectacle, known as line baptism, in which they submerged new whalers on their first voyage in the water.”

The sea god Neptune would then appear, with his "wife".

"Sometimes his daughter might even appear, or other 'women' in his entourage. These were men in costume presenting a stylised version of women.”

"The humour created a buffer between the men and reality, allowing them to experiment to some extent," says Ytreberg.

Strict discipline

The whalers could also use humour to take the sting out of various strenuous work duties. Ytreberg says that the working environment was characterised as hierarchical, dependent on strict discipline and fairly extensive control.

This characterised industrialisation in general:

"With larger machines that could perform more work, there was a need for more workers and an increased division of labour.”

“The harpooners, who worked on the ships that delivered whales to the land stations or processing vessels, had higher wages and status.”

“They became figureheads for the industry," says Ytreberg.

In the book, he writes that an experienced harpooner could identify species of whales based only on the whales’ blow.

"They could be considered a form of paid nobility, as they operated the harpoon cannons, which were an essential part of whaling.”

But everyone had a role to play.

"These were male communities in which they depended on each other to carry out very challenging work that could be exhausting, boring and at times extremely dangerous. Those types of communities becomes very close and are seen in retrospect as character defining.”

This article has been translated from Norwegian