"To be honest, I think water a bit boring," says Professor Mari Teigen, as we descend the stairs at the Institute for Social Research (ISF) for a photo shoot.

There is a red brick wall at the reception. "Perhaps you could stand there."

Teigen has worked in this building for many years, the last ten as director of CORE – Centre for Research on Gender Equality. Since the 2000s, she has been a powerhouse in gender research in Norway and internationally.

"When I recently turned sixty on 8 March, two colleagues held a wonderful speech. They said I may seem stern and harsh in certain situations, the kind of person who only drinks espresso without milk, but no! She guzzles hot and fruity tea!

Serious about gender equality

The interview at the Institute for Social Research is coming to an end, the atmosphere is relaxed, almost jocular. I snap a couple of photographs, stand next to Teigen and scroll through them on the display. "That one might work," I say, "even though you look a little serious."

Teigen approves of the image.

"I've stopped smiling when journalists interview me about my research," she says. “This is serious stuff: male dominance in the power elite, gender inequality and gender differences in education and working life, wage differences between women and men, and more recently: value polarisation.”

"Gender equality’s duty to give way"

If you search for "Mari Teigen" on the search engine Cristin, you get 268 results: books, anthologies, scientific articles, chronicles, lectures and reports.

I click on the oldest publication — a scientific monograph from 2003: Menn imellom: Mannsdominans og likestillingspolitikk (Among Men: Male dominance and gender equality politics), written with professor of political science Hege Skjeie.

"In the early 2000s, there was broad consensus in Norway that gender equality was the way to go. At the same time, we saw that the demand for gender equality often had to give way to other established values, such as freedom of religion and expression, freedom of negotiation between the social partners, and so on," says Teigen.

This is how the concept of "gender equality’s duty to give way" was born, and it has had a major impact and made Teigen a rising star in gender research.

"It was Vilhelm Aubert, one of my lecturers, who recommended that I contact Hege Skjeie, because she had started a project about women's entry into the top of party politics.”

"At its best, protest develops into a critical attitude.”

As part of the project, Skjeie was to interview many members of the Government and all members of the Storting – the Norwegian Parliament. Gathering information was massive job and she needed assistants.

They met in the office of the political scientist.

"We were the perfect match," Teigen said.

"When you have discussions with someone and feel uplifted, where what you say kind of becomes even more interesting, then it becomes stimulating.

Over time, they became a great academic duo.

"We enjoyed spending time together and had many discussions, and – although I've never felt I could hold a candle to her – I think she also found the discussions inspiring and fun," Teigen adds.

Teigen slips into the personal

When she entered the field, Teigen was sceptical about gender research, but now refers to herself as a gender researcher – "with some reservations".

In her master's thesis from 1990, she critically examined a concept that was almost set in stone in early women's research:

"Harriet Holter, one of the pioneers in Norwegian gender research, had written an interesting and important article that was on our syllabus. She argued that when women enter an arena, status and power disappear.”

Was patriarchy as tenacious and invincible as some areas of women's research would suggest? The 25-year-old student was sceptical.

"I think I've always had an inquisitive approach to assumed truths," says Teigen.

"And now we're slipping into something that I don't really want to do... something very personal... there’s always been a large part of me that wants to protest.”

"The woman that goes against the tide," was in the song booklet that her mother had prepared for her civic confirmations.

"At its best, protest develops into a critical mentality," says Teigen.

Ten litres of tea a week

One of the things of which Teigen is critical is the portrait interview genre itself.

The researcher likes to keep work and home life separate, and cherishes her private life, but the sheet in front of me is full of personal questions that will be asked... Do you have a type A or type B personality? What time do you go to bed? When do you get up?

Teigen tells me that she gets tired early, around ten thirty.

"To be fair, my kids think I have an A personality at night and a B personality in the morning.”

She gets up early with her youngest daughter (she has three children) and arrives at the Institute for Social Research between 08:30 and 09:00, either on foot or by bike.

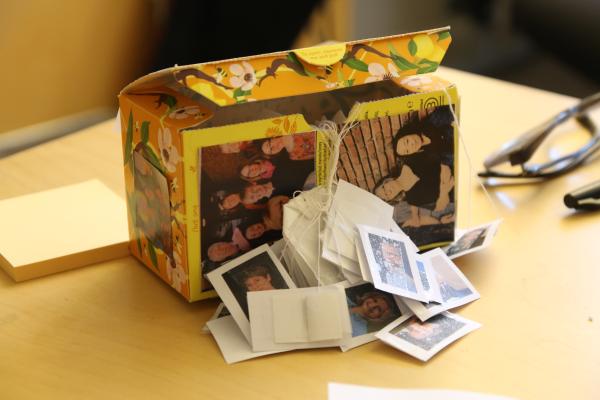

When I ask Teigen if she prefers coffee or tea, she gives a sly smile. She goes to find something on her bookshelf. Her tea drinking has become an inside joke at work:

"I just turned 60 and got this carton of tea from my colleagues — and that cup there," she adds.

"It holds half a litre!”

*Laughter*

"I'm so pleased that I've established a routine where I drink two cups of coffee in the morning and tea the rest of the day. Maybe four cups in the office, and a couple more when I get home.

Hyper-focused at lunchtime

The conversation conjures up the following image in my mind:

Mari Teigen enters her office with dynamite-strength morning coffee in her hand, nudges her computer mouse to bring her computer to life, tosses her jacket into the armchair in the corner of the room and sets about the day's tasks. Every time there is incoming email, the built-in PC speakers emit a quiet “pling”.

"I'm most productive in the morning and am usually in full swing right before lunch.”

Unfortunately, she often misses out on having her lunch break with her colleagues.

"The problem is, that's when I’m just getting going, and I think, ‘Okay, I have to go to lunch,' but then I think, 'I'm just going to...,' and before I know it, lunchtime is over.

Fortunately, she brings a packed lunch.

"It’s liver pâté and cheese – a real feast.”

“Are there peppers on the cheese?”

Teigen laughs.

"I'm starting to wonder what this interview is going to look like, but...”

CORE

Part of the reason she agreed to do the portrait interview was that CORE, the centre for research on gender equality that Teigen heads, had just celebrated its tenth anniversary.

"I can do this for the occasion of CORE's 10th anniversary," she wrote by email before we sealed the deal.

Armed with hard facts, Teigen, as head of CORE, has devoted her career to investigating how gender plays out in the structure of society — as opposed to what gender "is" on a philosophical level.

One of the things we have toiled a lot with at CORE are issues related to discrimination and gender segregation in the labour market," says Teigen.

Women are increasingly choosing non-traditional occupations, while men choose traditional occupations.

It has often been called the Norwegian gender-equality paradox:

"Even though Norway and the other Nordic countries have improved equality between men and women, it appeared that the labour market in Nordic countries was even more gender segregated.”

Together with others in her network, Teigen took a closer look at the gender equality paradox. They collected large amounts of data and ran analytics. The conclusion was striking.

It confirmed what Teigen and her colleague Jorun Solheim had asserted in an article in the Journal of Gender Research in 2006:

That it was not actually a paradox.

“In countries where the development of gender equality came at a later stage, women often stay at home. As a result, they fall outside the labour market statistics," explains Teigen.

*She takes a sip of tea*

"In the first phases of gender equality development, it’s common for women to enter female-dominated professions in, for example, the health and care sector. Gradually, they begin to spread into more occupations, as can be seen in the current trends.”

One of the main questions when it comes to gender-segregation in the labour market has been: why do women choose traditional professions?

"However, for many years we have pointed out that this is not the case. Women are increasingly choosing non-traditional occupations, while it is men who choose traditional occupations.

Responding to Jordan Peterson

Armed with what those at CORE call "policy-relevant" knowledge, Teigen is not someone you want to have on your back in a public debate:

"Jordan Peterson is in town", is how she begins an opinion piece in Dagbladet from 2018.

In a lecture, the Canadian psychology professor and debater used the gender equality paradox as evidence that there are inherent gender differences between men and women. He believed that when women become more equal and are given greater freedom, they use this to make traditional choices.

"That is actually wrong. The development of gender equality led to women more often choosing non-traditional gender roles, which is not so much the case for men. It is related to society's incentive structures," says Teigen during our interview.

The opinion piece is factual and concise, but does not pull any punches.

"I get so annoyed by Jordan Peterson because he pretends to present truths about the development of society, as if he empirically knows why things are the way they are," says Teigen.

Debates with more punch?

What does the researcher think about cancel culture?

Teigen opens the topic herself when I ask what she thinks about the youth of today.

"There is a lot of engagement among many young people today, but I also feel that there is a stricter sense of what one is allowed to believe or not believe.”

She is critical of today's polarisation.

However, as a young researcher in the early 2000s, Teigen was among those advocating more punch in the gender equality debate, which she considered far too tame:

"In Norway, we're always supposed to be in agreement. Everyone is ostensibly in favour of equality, so any opposition becomes harder to nail down. The major lines of conflict are rarely debated. The opposition is more coherent in Sweden, so the discussion is also more lively," she wrote in a Kilden interview from 2003.

"I wouldn't have said that today.”

"The social debate at the beginning of the 2000s was generally characterised by the disappearance of the contradiction. There was no longer anything to discuss, there was consensus everywhere.

Teigen currently sees a frightening development towards right-wing conservative and right-wing radical parties, as well as a more polarised left.

“I am more in agreement with those who say consensus is a good thing. It's important to have some things on which we can agree and converge," she says.

A leading question: would she rather be moderate or radical?

"Ten years ago, I would have said I wanted to be radical. These days, I want to respond moderately.

She believes that her change in attitude is not just due to age, but rather a growing concern about the current climate of debate.

"I also know that I tend to have very clear opinions, and that’s why I think I need to learn to be more moderate. I believe that the truth often lies in the nuances, and I don't think it serves society to hold very strong positions. How on earth can one be so sure of themself, when other sensible people think something else entirely?

Mari Teigen’s urge to protest is moderated by a desire to contribute to an open but nuanced debate, and societal development based on empirical knowledge.

A longer version of this article was first published in Norwegian.