Most people associate Viking raids with big, strong men with a full beard, horned helmets, shields, swords and spears. But new research indicates that women also played an important role in the Viking raids. They functioned as advisers, and they helped plan and arrange social gatherings for significant contributors and allies.

Aina Margrethe Heen Pettersen at Department of Historical and Classical Studies at Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) is writing her PhD thesis in archaeology. More specifically, her research material consists of Irish and English objects found in Viking graves in Norway from the period AD 800–1050.

Kitchen equipment was important

“In my thesis, I study the various roles and identities that emerged with the Viking raids in Ireland and England, and how these are reflected in the objects found in the Viking graves,” she explains.

The objects she analyses in her most recent article are bronze vessels, drinking horns, scoops, bowls and vats that have been used at large social gatherings, or banquets.

Some of the material was found as early as a century ago, but it has nevertheless received little scholarly attention, according to Pettersen. In her opinion, it is possible that these objects did not arouse much scholarly interest because they were ‘only’ thought of as ‘kitchen stash’.

“Many other types of objects are considered more interesting for research purposes, such as jewellery, weapons and religious objects. But by posing different questions to the material than what has been done so far, I explore whether it is possible to discover something new.”

According to Pettersen, these objects have been more significant than previously believed.

“It is highly likely that they have been used for serving in connection to banquets that were arranged both prior to and after the Viking raids. These feasts were important social and political arenas,” she says.

“We know that the objects are a result of the Viking raids, which are considered a masculine arena. But these objects have been found in women’s graves, and we may therefore assume that they belonged to and were used by these women.”

Expensive voyages

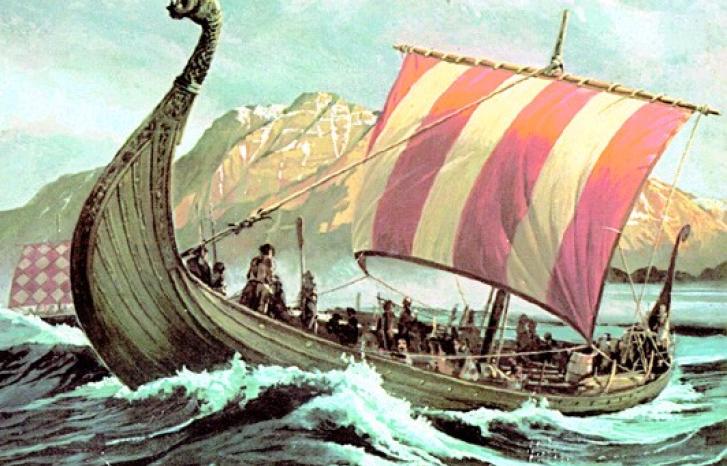

Pettersen emphasises that Viking raids demanded an enormous amount of resources. Shipbuilding and procuring the necessary equipment for the voyage required the workforce equal to hundred people working twelve-hour daily shifts for a year.

“Therefore, undertaking such journeys was a privilege reserved for the few. Even equipping smaller fleets of five to six ships required major resources and collaboration between several families. Thus, there were presumably families from the higher social layers of society that organised and were in charge of the raids,” she says.

The objects that Pettersen has examined were used for serving at these banquets, but they were also status symbols, as they were evidence of former successful raids.

“The objects have often been found in women’s graves that are well equipped, accompanied by other objects such as costume jewellery, brooches and pearl necklaces,” says Pettersen.

“Men were often accompanied by weapons in their graves, but the sets of cooking vessels and drinking horns that I have examined are only found in women’s graves.”

Adviser and alliance builder

But why were some of the women buried with these objects? What sort of role did the women play? These are some of the questions that Pettersen is asking.

“I believe that these objects are found in the graves because the people buried there held a special position in arranging banquets and building alliances prior to the Viking raids,” she says.

The women functioned as advisers, alliance builders and representatives of the household.

“The sets of vessels and drinking horns therefore reflect this important function. When goods were divided between the participants following a raid, it was only natural that some of the profit was accrued to these women.”

“These perspectives emphasise the role of the Viking housewife, in which the women functioned as advisers, alliance builders and representatives of the household.”

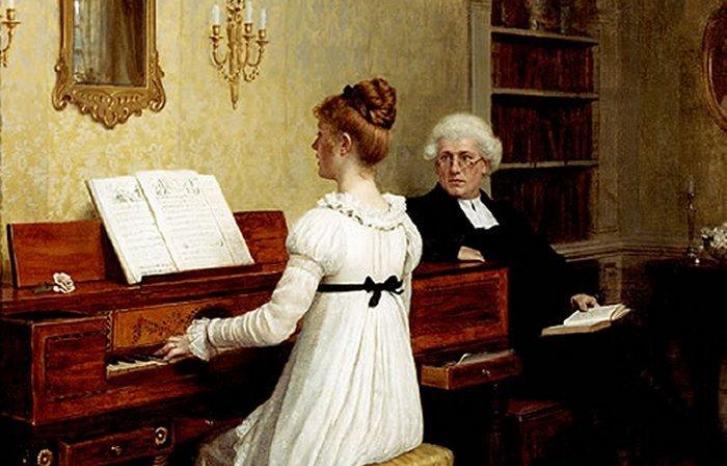

She explains that people gathered in the house when important decisions were made.

“The house was an open, social arena where the housewife held an important position. She ensured that the guests were made welcome, and her carefully chosen words to the guest while she filled the drinking horn could be decisive for the relation between host and guest.”

Were used for feasts

We must presume that the objects were meant for feasts rather than for everyday use, as they do not seem to have been much in use, Pettersen maintains.

“For instance, we see that the bronze objects are very thin. This applies to drinking horns, bronze vessels, scoops and small vats with bronze coatings. If they had been more in use, they would have been equally more frayed and we would have seen more traces of repairs than we do.”

She explains that the objects are richly decorated, which is also something that distinguish them from the equipment for everyday use.

“Drinking horns, for instance, are decorated with animal heads and vats with bronze coatings probably shone like gold and silver in the glimmer from the fire that would light up the feast.”

The objects were in major contrast to the locally produced equipment, which was mostly made of wood, iron and soapstone.

“They drew a lot of attention when they were in use, and they brought status to the owners.”

Hazardous voyage

Preparing for Viking raids also involved ritual preparations. There was a lot of superstition connected to the sea, Pettersen explains.

“We know from the sagas that the Vikings sacrificed to the Old Norse gods before they undertook long journeys. There are also examples of godheads carved into ship masts or ship tents,” she says.

“It was important to have close ties with the gods in order to secure the best protection as possible before they set sail for long journeys.”

We have found arrowheads and axes in women’s graves too.

And the journey along the coast of Norway and across the North Sea to the British Isles was long and hazardous.

“From Trøndelag, they first had to make their way along a perilous coastline down to the southwest of Norway before crossing the open ocean across the North Sea to the Scottish islands. This is a coastal area with powerful whirlpools and submerged reefs. Therefore, it was important to be on good terms with the gods.”

Pettersen explains that women have also played important roles in the performance of religious rituals and ceremonies before these journeys.

“For instance, we have one specific grave finding from Melhus in Overhalla. In this grave, a woman has been buried with a complete reliquary, which indicates that women could hold such religious functions.”

New perspective on the Viking Age

Marianne Moen, post doctor in archaeology at University of Oslo, claims that the views on women’s role in the Viking Age is about to change.

“I have experienced that my own research on this topic is received more positively now than just a few years ago,” she says.

“For a long time, the attitude has been that women were responsible for the house and worked inside, whereas the men worked outside. This view has not been much challenged.”

According to Moen, the image we have of how people lived in the Viking Age is characterised by how we live today, and this also applies to research.

“This is related to today’s political climate and our views on identities, which are changing,” she says.

“People are not just one thing or the other. And sex is not the only thing that shapes our identity. There are many indications that women could also be warriors and men could work in the household, also in the Viking Age.”

Moen brings up the Birka warrior as an example. As late as in 2017, researchers established that a Swedish grave finding from 1889 of a warrior from the Viking Age was in fact a woman.

“The fact that Viking women could also carry weapons is also supported here in Norway, as we have found arrowheads and axes in women’s graves too.”

Moen maintains that Pettersen’s research is important precisely because she poses new questions to old findings.

“Looking at the same material with new perspectives and posing different questions than what has been asked before is a fundamental part of the production of knowledge,” she says.

“We view our past through the lens of the present. We may of course argue both against and in favour of this, but it nevertheless contributes to nuance, and at best to new discoveries about the past.”

Translated by Cathinka Dahl Hambro.