“The standard specialist literature within the field is pervaded with Viking expeditions, kings, weapons, and battles,” says Viking researcher Nanna Løkka.

“If women are mentioned at all they are placed within an everyday context, with children, handicraft and domestic life. Thus, when the characteristics of the Viking Age are described, women are either left out completely, or they are given their own little paragraph, as they appear neither very exciting nor spectacular.”

In the recently published anthology Kvinner i vikingtid (“Viking Age Women”), 16 women and one man challenge this standard saga inspired account of the early Norwegian Middle Ages, which is characterised by raiding kings and chieftains. Løkka has edited the book in collaboration with Nancy Coleman.

Kvinner i vikingtid examines the various roles of women in a society where not only men possessed political power and influence.

The book shows that the role of women was not always a domestic one. On the contrary, they actively participated within various aspects of public life such as trade, textile production, medicine, and religious practice.

None mentioned, all forgotten

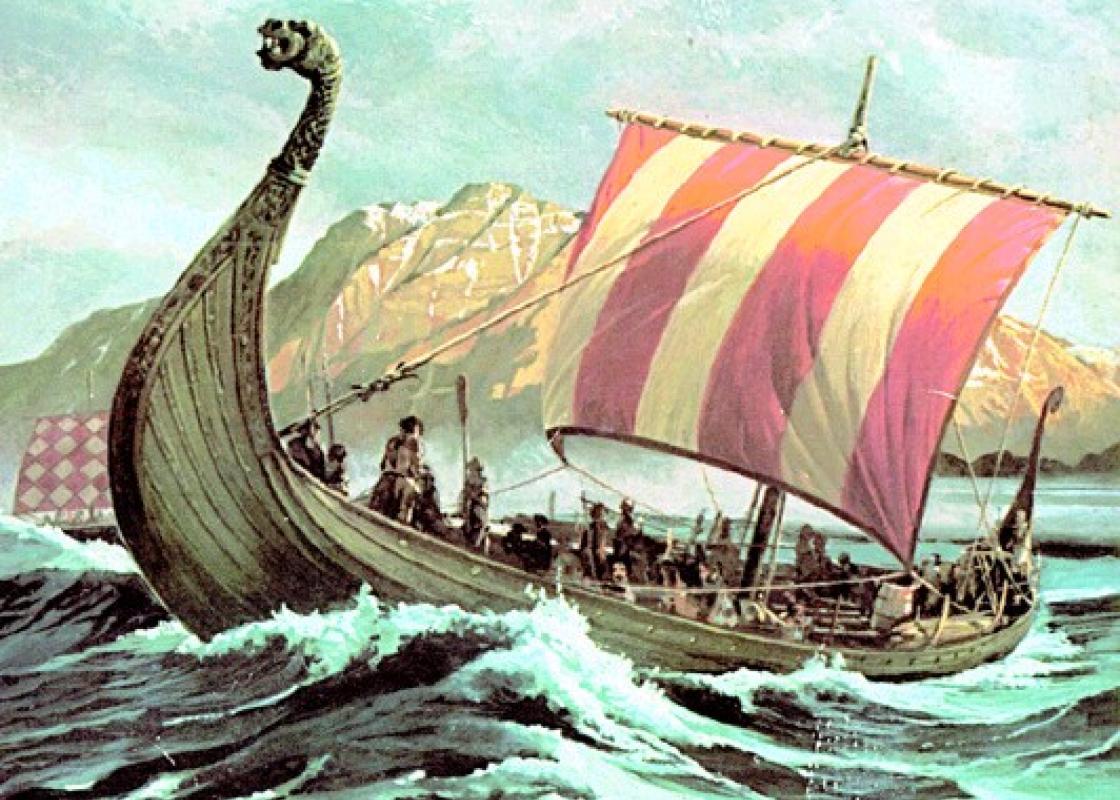

Both the sagas and the schoolbooks tell us show many benches (Norwegian: sesser) the master builder Torberg Skavhogg built for the rowers when he equipped the hull of King Olav Tryggvasson’s legendary longship Ormen Lange (“The Long Serpent”). The women who were responsible for weaving the sail, however, are not mentioned by name.

“The Vikings wouldn’t have reached England unless someone had equipped the ships with sails. It is a well-known fact that the Vikings were far ahead of their European neighbours in terms of maritime techniques. In an episode of the TV series Vikings, they make a big fuss about the ship’s anchor, but the sail is not mentioned with a single word,” says Løkka.

The textile production was probably organised hierarchically, where women supervised other women in extensive collaborative work.

“The larger Viking ships used 100 square meter sized sails. In order to produce that, the women needed 200 kilos of wool from approximately 2000 sheep, and it required hundreds of working hours. We are talking about more than just a small-scale family business.”

High school books are the worst

According to the researcher, the models applied to understand the Viking Age ignore the women’s impact and contribution. This is particularly visible in the high school history books.

According to Løkka’s examination, only one among the six most popular history books from the 1990s and 2000s provides its own paragraph on women.

“If women appear at all in the general literature on the field, they are usually depicted as the stereotypical “housewife” who is tied to the farm and the home, not as someone who participates in important social processes,” says Løkka.

In the standard accounts of the Viking Age, the farm is regarded as the smallest, yet most significant unit. Other important institutions in the Viking society are the family, the chiefdom, and the Thing.

The woman is usually associated with the farm and the private sphere, whereas the man is connected to public life. Hence, the gender roles are often described in terms of “inside” and “outside” in order to distinguish between men and women’s responsibilities.

“I’m not saying that the stereotypical representation isn’t feasible at all, but it contributes to a description of the Viking Age based solely on male activities. Most probably the Viking society consisted of other dividing lines and hierarchies where women to a larger degree ranked on top,” says Løkka.

The “housewife” as business manager

For example, recent research shows that being a “housewife” might involve major responsibility and hard work, particularly if the farm was of some considerable size.

The chieftain’s home at Borg in Lofoten, which is the largest known chieftain’s farm, was more than eighty metres long. That is only twenty metres shorter than the Nidaros Cathedral. A typical chieftain’s farm may have had a longhouse of approximately fifty metres. A banquet on such a large farm could easily involve 150 people, all of them expecting to be served food and drinks.

“Running a farm like that is like managing a medium size business. Thus, these women should rather be regarded as business managers than mere housewives,” says Løkka.

With this in mind, one may therefore ask whether this type of feast actually belonged to the so-called private sphere. At these banquets, contracts and deals were made, politics was developed, and alliances were formed.

If the food or drink was unsatisfactory it could cause diplomatic crisis or disgrace. Therefore, the women who cooked and served the meals held an important public function.

According to Løkka, categories like inside/outside and private/public have probably become antiquated due to recent research.

Malevolent Viking women

It doesn’t make things better that the women who did position themselves at the top of the male warrior hierarchy were often severely condemned by the later saga writers. This was the case with Queen Gunnhild, who according to tradition received training from Sami magicians. Allegedly, she took over the leadership of her sons’ army when her husband Eirik Blodøks (Eric Bloodaxe) was driven into exile and subsequently killed.

Alfiva, the de facto Norwegian ruler in the beginning of the eleventh century, received an equally bad reputation, becoming highly unpopular after introducing new legislation and a new tax system.

Viking reverie as nation building

Nanna Løkka emphasises that in many ways the term Viking Age is a nineteenth century construction, which was formed along the lines of the era’s prevailing national romantic ideals.

For instance, historian Jørgen Haavardsholm has noted that the term Viking Age can be connected to a political process in which the goal was to create a nation with a proud and common past where the Vikings served as masculine and unyielding heroes and adventurers.

“An entire period and society has been connected to the Viking raids. In reality, however, only a small number of the men actually went on Viking raids. It has nevertheless added masculine value to the era, and consequently the female half of the population has been neglected,” says Løkka.

Farewell to the Viking Age?

The national romantic heritage is one of the reasons why a new generation of historians preferred to use the more neutral and European term Early Middle Ages in the four-volume history work Norvegr from 2011. Archaeologists, on the other hand, have mainly preferred the term Late Iron Age.

“Is that the way to go?”

“I ended up using the term Viking Age primarily because I want people to understand what I am working with. Moreover, the Viking Age sells and attracts attention. But there is definitely an ambivalence there.”

Translated by Cathinka Dahl Hambro.

Nanna Løkka holds a PhD in History of Religion and works at Telemark University College. She has edited the new anthology Kvinner i vikingtid (“Viking Age Women”) in collaboration with Nancy Coleman.