“Simone de Beauvoir was regarded as an attachment – Sartre’s disciple and mistress – and perhaps as a little scandalous. Both aspects contributed to undermining her position as an intellectual,” explains Ida Hove Solberg, PhD fellow at the University of Oslo.

Solberg has written her PhD thesis about how the famous philosopher and feminist Simone de Beauvoir is represented in Norwegian public discourse.

“When she and Sartre travelled together in Scandinavia in 1948, de Beauvoir was referred to as his ‘secretary’ in the literary journal Vinduet (The Window),” says Solberg.

No room for intellectual women

Solberg demonstrates how the public discourse on de Beauvoir develops over time and becomes a mirror of Norwegian society and a changing feminist movement. From initially being referred to in more or less sexist terms, de Beauvoir eventually obtains an independent status as writer and philosopher. In the 2000s, she was considered a popular cultural and feminist style icon for young women, business leaders, and executives alike. She was even used as a model for the autumn fashion collection in the 1990s, according to Solberg.

“First and foremost, this shows how we regard intellectual women. Our view of them is reflected in the way in which they are received,” says Solberg.

During the gender conservative 1950s, there was no room for intellectual women. In France, de Beauvoir was referred to as sexually deviant, frustrated and jealous. Many thought she looked down upon the feminine when she described women’s lives as passive and marriage as oppressive.

It ‘always constitutes a kind of rape’, she writes about the sexual encounter between man and woman in The Second Sex. The home is described as a ‘cramped room’ that ‘limits her horizon’, and reduces nature to become of the ‘dimensions of a pot of geraniums’. Such formulations often resulted in accusations of her being unwomanly.

According to Solberg, the French-Norwegian journalist Nicole Macé challenged this in the national newspaper VG in 1961.

Macé described de Beauvoir as a significant thinker, far from being a cold intellectual. On the contrary, Macé saw de Beauvoir as warm and emotional in her depictions of Sartre.

A popular feminist

Although Macé’s description was positive, it illustrates that de Beauvoir does not escape characterisations.

“In the first translation of The Second Sex, we get the impression that the translator is trying to erase the image of de Beauvoir as a harsh feminist,” Solberg explains.

“She was made popular. Sarcasms and cynicisms are downplayed.”

What is included in the final translation was determined by politics and ideology.

Solberg has studied the first Norwegian translation of The Second Sex, which appeared on Pax Forlag in 1970. Contrary to the Danish translation that appeared five years earlier, the Norwegian version was radically abridged. According to Solberg, the translation says more about Norwegian society than about Simone de Beauvoir herself.

“Everybody wanted a feminist classic. In the ideological climate at the time, existential philosophy took up little space, and much of what was said about sexuality was cut out. The publishing company wanted to reach the masses,” says Solberg, who has gained access to the correspondence between the translator Rønnaug Eliassen and the publisher from Pax’s archives.

Fragmented feminist movement

In the desire to create a feminist who was passable for the many rather than the few, the publisher considered it inexpedient to publish a complete edition of nearly 900 pages.

“What is included in the final translation was determined by politics and ideology. Nevertheless, it paints a picture of a fragmented feminist movement,” says Solberg.

The ideological landscape encompassing the reception of de Beauvoir in Norway in the 70s was characterised by the fact that a majority of the feminist movement belonged to left wing politics. They were more preoccupied with issues such as equal pay, work and day nursery coverage than sexual liberation.

“The translator Rønnaug Eliassen, who was an active left-wing feminist herself, was probably not as interested in sexual politics and the historical aspect as she was in work and day nursery coverage,” says Solberg.

In Eliassen’s translation, there is a direct line from how women’s lives are moulded in childhood and adolescence until she becomes married and independent.

“A fairly short path from upbringing to independence,” according to Solberg.

Pragmatic feminist movement

Historian Trine Rogg Korsvik has written her PhD thesis on the Norwegian and French women’s movement of the 1970s and 80s. According to her, the women’s movement in Norway acted strategically in order to succeed.

The Norwegian feminist movement was more popular and stout, in line with the Norwegian popular movement.

“In the 1960s’, sexuality wasn’t the most prominent issue of the women’s movement. They knew they would not be taken seriously if they fronted sexual political matters that were still tabooed in Norwegian society.”

Korsvik refers to the previous years before the translation of The Second Sex appeared, when there was a major outcry in Norwegian public discourse over the author Jens Bjørneboe’s novel Uten en tråd (‘Without a Stitch’). It revolves around a young woman with sexual inhibitions who receives help from a doctor to explore her own sexuality. The book was banned in Norway. Due to the political climate, idealistic concerns may have yielded to pragmatic concerns when Pax and the translator chose which parts of The Second Sex they wanted to publish.

See also: Toril Moi: Feminist theory needs a revolution

Avoided questions of sexual character

According to Korsvik, the Norwegian women's movement generally acted very respectably in this period.

“Apart from contraceptive counselling, questions concerning sexuality were rarely addressed. The Norwegian Association for Women's Rights (Norsk Kvinnesaksforening) did for instance not address issues such as lesbians’ situation until the late 1970s. Nor were they preoccupied with pornography and prostitution.”

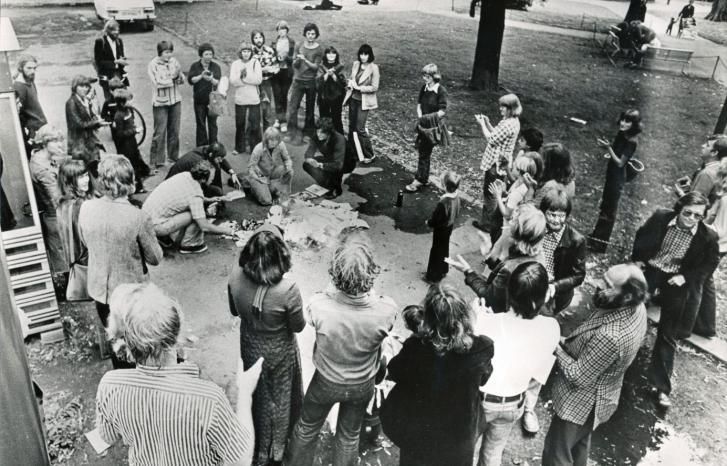

It was different with the New Feminists. In 1972 they mobilised around slogans such as ‘no forced fucking’ and ‘we want to be on top’. But such explicit slogans were far from endorsed by the whole women's movement. Particularly the activists of the Women’s Front (Kvinnefronten) were afraid that this kind of tough slogans would alienate working class women.

Trine Rogg Korsvik emphasises that major parts of the Norwegian women’s movement were far more down-to-earth than their French fellow-sisters, who were more avant-garde.

“Compared to the French feminist movement, the Norwegian women’s movement was more popular and stout, in line with Norwegian social movements,” says Korsvik.

She explains that whereas the French feminists were very revolutionary and uncompromising after 1968, Norwegian feminists had a more pragmatic stance towards cooperating with other organisations that didn’t necessarily share their view in other matters.

“This pragmatic stance was typical of the broad popular mobilisation against Norwegian membership in the EEC in 1972, as well as of the mobilisation for “free abortion” – the main demand of the 1970s feminist movement.”

More relevant than ever

In the 1940s and 50s, the images of de Beauvoir characterised her as Sartre’s ‘other’ – the secretary, the lover and the disciple. In 1965, the Danish translation of The Second Sex paved the way for new images of de Beauvoir. We were shown the philosopher and the feminist, according to Solberg.

“A new development began in the 1990s, when de Beauvoir again became popular in Norway. Young people flocked to the universities to study philosophy and gender studies, which were becoming institutionalised disciplines at the time.”

Solberg points out that the internationally renowned de Beauvoir expert and professor of literature at Duke University, Toril Moi, contributed to making her relevant once more.

“Books such as Simone de Beauvoir: The Making of an Intellectual Woman (1994) really brought the French philosopher and feminist thinker back into the public discourse.”

In 2000, the complete translation of The Second Sex finally became available to Norwegian readers, in Bente Christensen’s translation.

Toril Moi recognises the serious work of examining the two Norwegian translations and the reception of Simone de Beauvoir in Norway. She has noticed that de Beauvoir is highly popular in Scandinavia:

“De Beauvoir is more relevant now than ever before. She writes about the body as a concrete situation, about women and freedom, the individual’s right to express oneself sexually on one’s own terms, and she demonstrates how sexist logic works.”

Translated by Cathinka Dahl Hambro.

Read more about the feminist movement in the 1970s in France and Norway here: Burning porn in Norway, fighting rape in France

French feminist, philosopher and writer (1908–1986), especially known for her work The Second Sex (1949), which is considered a feminist classic. It first appeared in Norwegian in 1970, in a highly abridged edition. She holds a central position within French existentialism, together with philosophers such as Jean Paul Sartre and Albert Camus.

PhD research fellow in translation studies at Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages at the Faculty of Humanities, University of Oslo.

On 20 April, she will defend her PhD dissertation Traveling Feminism. Simone de Beauvoir and Le Deuxième Sexe in Norwegian Translation and Reception.

She is a member of the research group Traveling Texts, which studies the way in which values and ideologies affect, and are negotiated in, translations of foreign literary works.