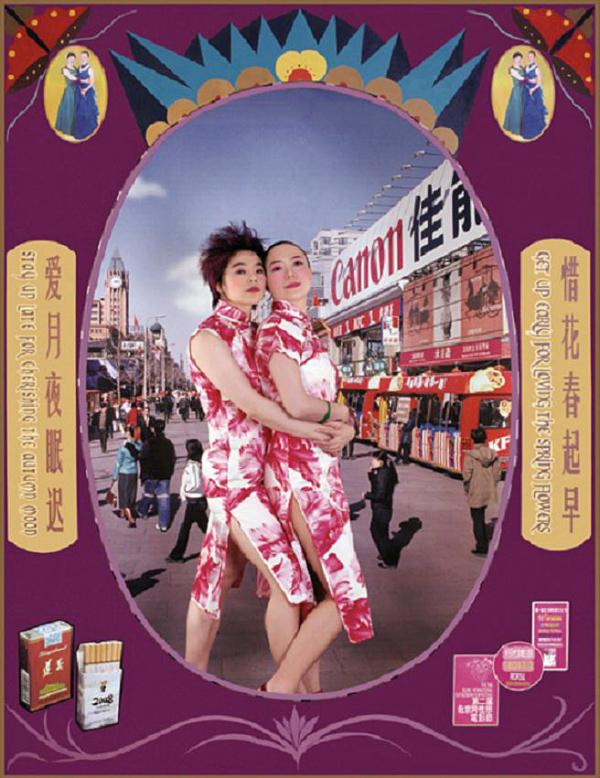

It’s a hot summer evening in 2005 and Elisabeth Lund Engebretsen is at the women’s bar West Wing in Beijing. She’s the Norwegian lala researcher – the lesbian researcher. A year ago it would have been hard to find a women’s bar like this in Beijing, but now you can find anything from lesbian badminton groups to lesbian debate groups.

The women at West Wing sing karaoke, there’s thick smog in the bar and Engebretsen is talking to Shuchun. Shuchun is a T, that is a Tomboy. She works in the media, she’s a lesbian and she has a gay boyfriend that she met through a website for so-called façade marriages, also known as contract marriages.

Shuchun and her boyfriend plan to get married, since that is what is expected in order to satisfy parents and society. But lately they’ve argued a lot. They don’t always agree in terms of values and the direction of their future life.

Another T joins the conversation. She says that she thinks the lala scene is chaotic and that she’d prefer something more normal and stabile. She recently broke up with her girlfriend who married a man afterwards.

More women join the conversation and they come to the conclusion that there are two factors which make it difficult to be openly gay in China: the political situation and the traditional Chinese view of women which forms the basis of the entire society. Women should get married and have children.

Women lose more

The book Queer women in urban China about lesbian lives in China is the first in its field. It is based on Engebretsen’s two-year-long field work in Beijing from 2004 to 2006, as well as on several later stays in China and regular contact with the gay communities over the years.

Although there’s a pressure to get married for men as well – who experience a bigger pressure to produce a family heir who can continue the family name and provide for the family – women are the biggest losers in these contract marriages, according to the researcher.

“Women lose their autonomy in a way that doesn’t affect men to the same degree. As a wife you have the responsibility to look after and take care of both his and your own parents as well as other relatives. The home and the household is the woman’s responsibility. Whereas marriage may be a ‘boost’ in the husband’s career it may be the opposite for the woman. She may easily be ignored the next time someone is promoted at work – after all she will soon have a child to look after.”

Maintaining the façade

One of the contract marriages that Engebretsen is familiar with illustrates the problem:

She, a lesbian, still lives in her home town. Her gay husband has moved to Beijing and lives there with his male partner. She runs her own business and makes good money, and she has a girlfriend. But she is the one who still lives in her home town and thus have to maintain the façade.

“She has to visit his family and take care of them since that is part of her responsibility,” says Engebretsen.

“Her parents have probably realised that the girlfriend who always comes along is more than just a friend, but they buy into it. As long as people are not confronted with the truth everything is ok, at least for a while.”

The childlessness has to be explained away as best as possible; that it is too expensive, infertility, things like that.

How many people who enter into these façade marriages is uncertain, and the figures are difficult to come across. But everybody talks about them.

“Many people say they want to do it. They spend much time on the web forum and internet sites where one can find a suitable partner. But finding someone to share their lives with is hard. Several of my contacts who have entered into these marriages are divorced within a few years.”

As straight as possible

Moreover, it takes more than just a man and a woman to get married in order to maintain the façade. This is clearly expressed in the internet adverts.

The gay men want a feminine wife. The gay women want a husband that is not too feminine.

“Sexuality as such is not the problem, it’s overstepping the gender stereotypes,” says Engebretsen.

“If someone doesn’t behave according to the stereotypes, they’re potentially gay. And since these marriages are all about making others believe that you’re straight it is important to live up to the expectations.”

In reality it is difficult to find the stereotypical perfect partner. According to Engebretsen’s informants it is actually quite often the more masculine girls and the more feminine boys who seek a way out in these contract marriages. They said that feminine lesbians often end up marrying a straight man.

Gay men who marry straight women are, according to Engebretsen, a well-known problem.

“Wives of gay men have become a social category in society. They’ve formed their own activist organisations who sometimes promote gay marriage as a positive thing which is morally better than misleading straight women.”

Tomboy or wife?

When Engebretsen commenced her field work in 2004 many didn’t use categories in order to describe themselves.

“They spoke about gender based roles, about masculine and feminine. They used T for Tomboy and P for po, which means wife. Gender roles were more important than sexual orientation and identity,” says Engebretsen.

And they weren’t lesbian, they were lala.

“What is the difference between lala and lesbian?”

“In a way it’s the same thing. But lala is not used as a personal identity in the same way as lesbian is. The way I see it it’s a wide social category which also include sexual orientation, but sexual orientation is not always the most significant aspect.”

See also: Hidden stories about sex and gender in the Norwegian Queer Archive

Almost normal

Being openly and visibly gay has been an important political strategy in the western struggle for gay liberties. Challenging the establishment, breaking with the norms and embracing the alternative have been the main aims. Being gay is part of an identity. Most of the women in Engebretsen’s research just wanted to be normal.

“I thought I was going to China in order to study identity politics, a regular queer study. But most of my informants were against identity based activism,” says the researcher.

“They thought it risky, and they thought it marked them out as abnormal. Their wish to live ‘normal’ lives, in terms of living up to family responsibilities, became difficult. Yet paradoxically they sought activist and social groups in order to break out of isolation and frustration,” says Engebretsen.

Moralising queer research

Her book is a contribution to the growing critique of western queer and lgbt research, which, according to Engebretsen, is often quietly moralising. Being different and transgressive is considered positive and expected, it is considered the right way in a western, mainstream perspective. Wanting to live a ‘normal’ life is negative and considered traditional, ignorant and anti-queer.

“For Chinese lalas it is important to be normal, and this needs to be taken seriously by scholars. It doesn’t mean that they’re brainwashed or old fashioned. ”

“Activism is about wanting to change and improve something, and it may be subtle and indirect,” says Engebretsen.

For instance in the social «lala salon» where women get together and talk about their lives the personal becomes political.

“However, as long as the Chinese authorities continue to ignore the lgbt population by not addressing the massive social stigma towards homosexuality in society, subtle strategies have a very limited collective impact,” says Engebretsen.

Not necessarily controversial

Homosexuality is not mentioned in Chinese criminal legislation, but it was considered a mental disease until 1997. According to Engebretsen, one may, however, say that homosexuality has been criminalised. Other legislation has been used in order to prevent something which is considered morally reprehensible within the public sphere.

“But gay activism is not considered a big problem,” says Engebretsen.

“As opposed to parts of Eastern Europe and several African states, homosexuality is not a politically sensitive theme in China. What is really sensitive in China is religious and ethnic minority activism. The gay activists have got off lightly compared to underground Christians, Muslims or Tibetans.”

Most Chinese would probably still think of homosexuality as a disease, that is, if they’ve heard of homosexuality in the first place. But things change fast.

“People travel and they have internet access. They see that gay people get married in the US, they know Elton John and Ellen DeGeneres. This alters how people think about how to be and how to live.”

At the same time, there are huge political tensions in China and the class distinctions are increasing. Not to mention the male population who are struggling to find wives because too few baby girls are being born.

“Things are both progressing and regressing. More freedom and less freedom. And there are a lot of debates going on concerning what is a good and morally correct life. After several years of progress for women and equality there’s now a setback,” says Engebretsen.

Less visible, more varied

Activism flourished when Engebretsen did her field study, much because of the internet. However, the researcher has witnessed a setback during the last years due to the financial crisis, a new government and the severe regulations which took place before the Olympic Games in 2008.

“There are no more lala bars in Beijing. Lala salon has moved to a private apartment outside the city centre. The public visibility has decreased and more is happening online.”

Yet there is more variation in the queer scene today than it was ten years ago. More support from abroad has provided more resources for some groups. Documentaries are being produced, people are taking action for gay rights such as same sex marriage and foreign media write about the Chinese gay community.

“However, it is often male homosexuality which receives the most attention and resources. The female networks are struggling,” says Engebretsen.

According to the researcher there is still a lot of scepticism towards making sexual orientation a political matter among lesbians in China. But the new, younger generation is less scared. The fear is not an integral part of them, as it is with the older generation.

“They have a different attitude towards what is important in life both concerning the individual end the collective. They are impatient and less willing to make compromises.”

“Times change quickly. For instance, the lgbt network in China is now increasingly cooperating with similar networks abroad, particularly in Asia. But it is impossible to predict how the strategies and the social networks will develop in the future.”

Translated by Cathinka Dahl Hambro.

Elisabeth Lund Engebretsen is an anthropologist. She is currently working as a researcher at Asian Cities Cluster, the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS) in Leiden, the Netherlands.

Today Engebretsen is studying young educated people who struggle to enter the labour market in China, and the growing class distinctions in the country.

She is also editing an anthology about activism and queer research in China, including contributions from Chinese authors. The anthology is expected to be published this year.

The book Queer women in urban China – An ethnography was published in 2013 as part of the book series Routledge Research in Gender and Society.