The singer, artist and social commentator Ruth Reese (1921–1990) left a significant mark on Norwegian public life.

A search of the National Library of Norway's digital library yields 11,000 hits covering a huge range of topics: from concert announcements at Astoria to indignant opinion pieces.

"You can almost track her movements through the newspaper articles," says researcher and social anthropologist Michelle A. Tisdel.

In 2021, a year after the Black Lives Matter protests were triggered by the murder of George Floyd, Tisdel decided to explore the roots of anti-racism in Norway.

“I started with the 1970s and 80s, a time when the first anti-racist magazine Immigranten was launched in Norway, in 1979.”

Social anthropologist and researcher at the National Library of Norway.

Lead curator for Black History Month Norway

Contributing author of a chapter in the anthology "Litterære rettighetskamper".

The roots of anti-racism

Ruth Reese came to Norway in 1956 to work as a musician. She then met her future husband Paul Shetelig and remained in Norway.

Michelle A. Tisdel has been involved in disseminating Ruth Reese’s story in various contexts, including in Black History Month Norway, an annual project that explores and communicates African and Afro-diasporic history in Norway.

Reese was also a writer, although was less known for that, and became an active member of the Foreign Women's Group, founded in 1979.

A recurring theme in Reese’s activism was the critique of racist stereotypes and tropes in culture and entertainment. For example, she spoke out about the use of "blackface" as early as 1960, both in her writing and through multiple complaints to Norway’s national broadcaster NRK.

In a unique position

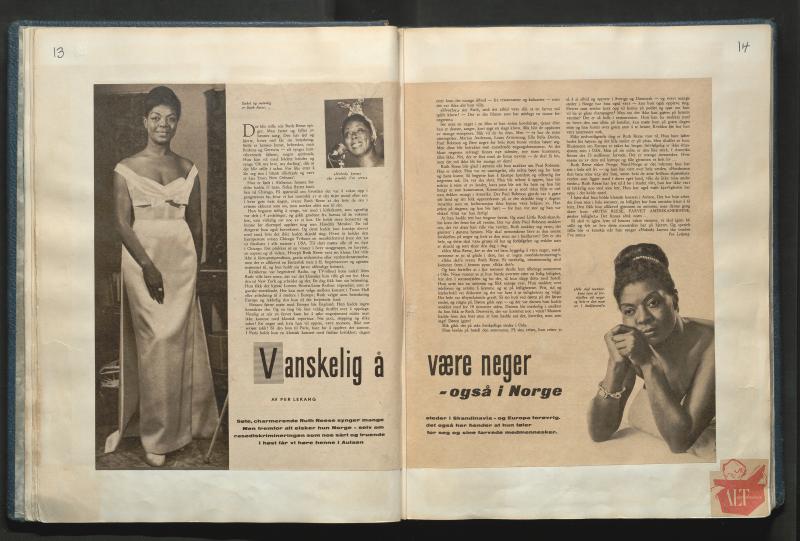

One of the earliest extensive interviews with Reese appeared in the magazine Alt for damene in 1958.

“In the interview, she is one of the first people to describe what it was like to be a black woman in Norway and in the USA.”

Tisdel believes that Reese felt a strong sense of responsibility and duty to take action against the racial violence from which she fled as a three-year-old.

“I believe she was in a unique position, with the experiences she had from the USA and then ending up in a more neutral country like Norway.”

Felt alienated

Just a couple of years after moving to Norway, Reese became active in the Student Society's fight against apartheid in South Africa. She maintained close ties with her American colleagues, friends and family. This made her an important source of information and knowledge about the civil rights movement in the USA, Tisdel explains.

According to Tisdel, Reese was deeply affected by news of racial discrimination and racially motivated violence in the USA. This is reflected in an opinion piece "Vår hud er sort" (Our skin is black) in the newspaper Dagbladet. In the article, she describes how reading about the abuse of black people in the USA affected her sense of belonging.

“Reese describes sitting on a train from Stockholm to Oslo. She was enjoying the journey and view from the window. She then read an article about the sexual assault of a black girl by a white man from the USA who escaped the death penalty. She was furious.”

“Not just because of the case itself.”

“Suddenly, Reese felt that she was black. She felt alienated.”

Activism came at a cost

In 1960, Reese toured with her lecture "Racial hatred and democracy", which addressed conditions in the USA.

“She believes that by giving people the facts, a new perspective, explaining the situation from her point of view, and providing them information they don't already have, she could change people’s opinions.”

However, it came at a cost. In her autobiography, she acknowledged that she is "fully aware" that her activism has impacted her artistic career.

Filling gaps in the archives

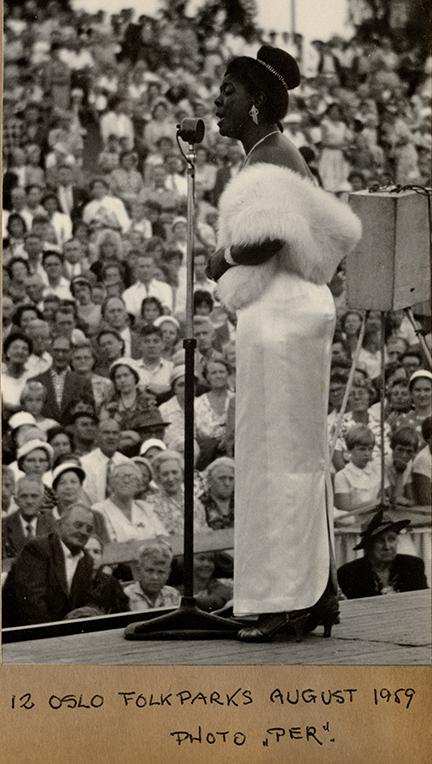

Ruth Reese attracted attention both as an activist and as a communicator. She made headlines in newspapers and magazines, and kept records of it all, likely with the help of her husband, Paul Shetelig.

Tisdel explains that Reese's albums also contain material from the USA and Europe, suggesting that she began documenting her life before moving to Norway.

It is an important historical archive for those wanting to learn more about the society in which she lived, and about her as a person and as a minority.

Researching the history of minorities can be challenging in itself. What has been considered worthy of archiving has changed over time, and this often leaves major gaps when researching the experiences of minorities in a historical perspective.

“There is too little archival material from the perspective of people with minority backgrounds.”

“Or to put it another way: that kind of material doesn't find its way into many archives," says Tisdel.

Private archives such as Reese’s are therefore invaluable.

Her albums not only include clippings from Norwegian newspapers, but also articles from the USA, personal photos, poems and short stories, and concert programmes.

The material was preserved by activist Fakhra Salimi and the MiRA Centre. Salimi also became a close friend of Reese and they were both members of the Foreign Women's Group, the precursor to the MiRA Centre. The collection is now housed at Oslo City Archives.

Requires a special effort

Historian Runar Jordåen from the Norwegian Archive for Queer History recognises the challenges of researching minorities.

"Those of us working on the archive are standing on the shoulders of a global grassroots movement," he says.

Museums and institutions had long overlooked crucial parts of history.

“It's not a neutral activity to decide what cultural heritage to preserve. It comes down to what you believe to be important.”

"Queer archives were established in a number of countries from the 1970s onwards," says Jordåsen.

“One of these pioneering archives is South Africa's GALA Queer Archive," he says.

“They weren't the first, but they were early to establish their own institution. Others then followed suit. Personal items and stories are important, and the archive documents both the present and the past.

"The emergence of dedicated archives for labour history, women's history, Sámi history and queer history exemplifies the fact that if you want to preserve a diverse cultural heritage, you need to make a special effort for minorities," he points out.

"When the Norwegian Archive for Queer History was established, ethnic minorities were barely represented in the collections they first collected from the 1960s and 70s," says Jordåen.

He would like to see more research into the relationship between Rolf and the American actor Earl Hyman, who became a couple with the Norwegian Rolf Sirnes in 1954. Hyman played Othello at The National Theatre and also featured in the Norwegian film "The African" (1966). The film depicted the racism a South African student could face when coming to Norway.

It is not known whether Hyman and Reese knew each other, but it is certainly not unlikely, says Jordåen.

A protagonist

Michelle A. Tisdel finds it interesting that Reese herself likely considered her archive to be important.

"Ruth Reese probably saw herself as a protagonist," says Tisdel.

“She wanted to make a difference.”

Tisdel sees traces of this in what Reese has left behind in her writing, not only in her articles, but also in her poems and short stories.

According to Tisdel, A number of these adopt a "self-historicising perspective". By that, she means that Ruth Reese wrote about historical events as if she were a participant in them, or was a contemporary witness.

“You relate to an established framework of historical events, and then write yourself into it. By doing so, you can help influence the narrative of society.”

This creative approach also became apparent in an interview during a feminist book fair in 1986: "Black female writers need to write in order to change reality," she stated at the time.

Reese portrayed much of herself in her writing, without necessarily making it clear that it was her own personal experience. However, that becomes evident if you read her autobiography.

“You are an anthropologist, not a historian. As an anthropologist, do you work differently with this material than a historian would?”

“I am keen to highlight her relevance from a contemporary perspective. Some of the things she writes about equality and belonging are things you could hear an artist say nowadays. She is an important part of the history of anti-racism in Norway.