The literary scholar Anna Young based her doctoral thesis “Unaccountable Violence: The Murderous Child in the British and American Novel, 1954-2003” on five stories about children who kill.

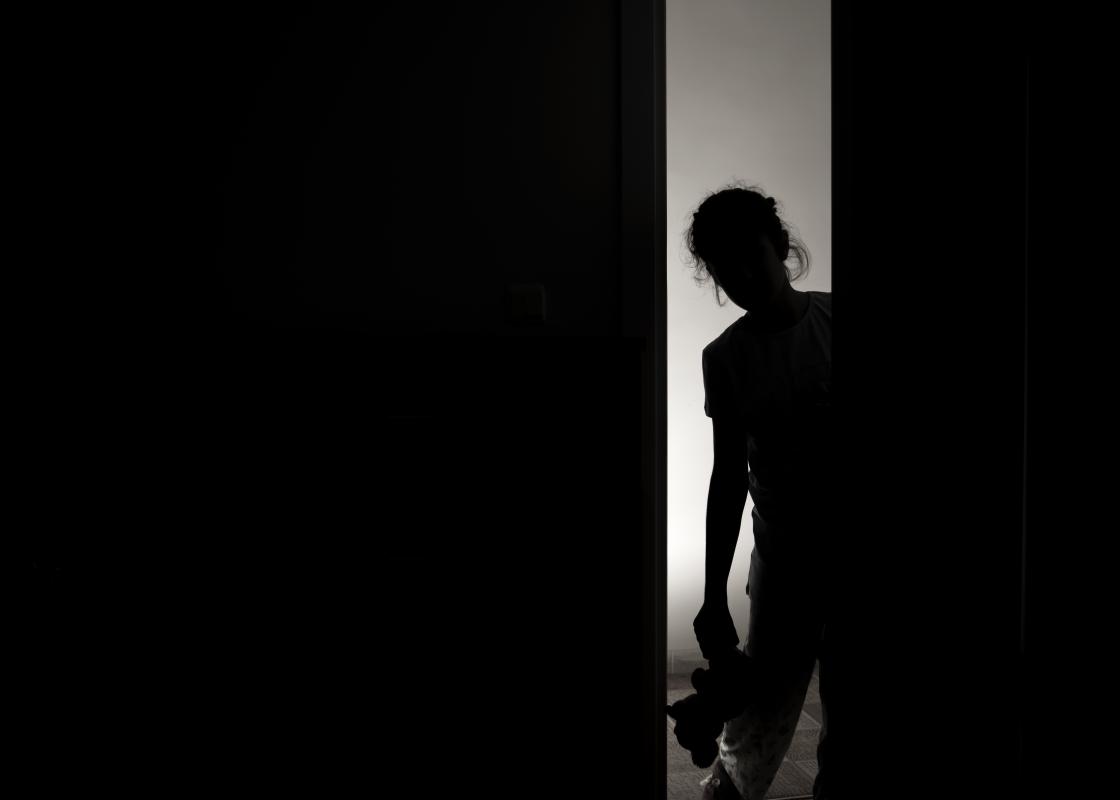

"Children are often understood as more 'natural' than adults and are therefore associated with positive qualities such as innocence and authenticity. That being said, there has been an underlying fear in culture about children’s primitive side, and the idea that children need to be moulded so as not to get out of control," says Young.

As she began to familiarise herself with how children are portrayed in adult literature, Young noticed something interesting:

"In the few books where children play the main character, they tend to be a bit evil or dangerous.”

Why is that?

Anna Young based her doctoral project on five British and American novels published between 1954 and 2003:

- The Bad Seed (1954) by William March

- The Lord of the Flies (1954) by William Golding

- We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962) by Shirley Jackson

- The Wasp Factory (1984) by Ian Banks

- We Need to Talk about Kevin (2003) by Lionel Shriver

Killer with tapdancing shoes

Young believes that in the 20th century, particularly in the post-war period and beyond, the notion of the idealised child has become much more central to our lives than it was in the past.

"In parallel with this, from the 1950s onwards, we see more and more depictions of evil, wicked children. They have become a kind of pop culture trope.”

Literature and film act as an outlet, a place to express slightly more ambivalent feelings about children.

In her thesis, Young explores how ambivalence is expressed in the descriptions of murderous children in five British and American novels published between 1954 and 2003.

Among the children is eight-year-old Rhoda Penmark, the main character in the book The Bad Seed (1954) by William March. In many ways, she is the perfect child. She achieves good grades at school, follows the rules to the letter, wears beautiful dresses and never gets dirty.

Adults think she is charming and wonderful, says Young, but she makes others feel uncomfortable. In particular, several children in her class notice that there is something earie about her.

"There's something theatrical, almost performative about Rhoda. She is reminiscent of a child star and is extremely feminine.”

When one of her classmates wins first prize in a handwriting contest and refuses to give her medal to Rhoda, Rhoda beats her to death with a tapdancing shoe. When a caretaker in the neighbourhood gets on the trail of the young killer, she kills him too, by setting fire to the room where he takes his afternoon nap.

Killer children remain an enigma

"When I started the project, I was interested in how authors accounted for what happened in the story. What caused these children to do these terrible things?”

Were the children born like that? Did they have bad parents? Or was it societal influence?

The children are often seen from the outside, so you never quite know what they are thinking.

The thesis mainly argues that the authors of the five books do not really provide an answer as to what drives children to commit the terrible acts.

In her analysis, Young has looked at what literary science calls narrative form.

"That can be as simple as looking at who's telling the story," she explains.

"It's consistent throughout all the books that you never quite see the child's perspective. The children are often seen from the outside, so you never quite know what they are thinking.”

The literary form reflects children's general position in society during the period in question.

"The child isn’t given the chance to speak or isn't regarded as a 'competent' narrator. We talk about children, not with them.”

In some of the books, the children themselves narrate the story. You might expect that this would provide a better explanation, but that is not necessarily the case:

"They only tell part of the truth, or say things that aren’t true. As a reader, you don't really know where they stand.”

The killer children remain an enigma.

Children are queer

Young has long been interested in how children are portrayed in adult literature and what the stories say about gender roles in society.

In her master's thesis on children portrayed in literature from the Southern United States, she investigated, among other things, what happened when characters reached puberty and stopped being "tomboys.”

"There’s a certain freedom associated with childhood, and girls in particular have often had the opportunity to be more experimental," says Young.

"As a girl, you can be more masculine, and might even be cheered on for climbing trees and wearing scruffy clothes. However, there comes a point where you transition into teenage life, which means adapting to society's gender norms to a greater extent.”

Children's scope of freedom and ability to act in an unruly manner lead theorists such as Kathryn Bond Stockton – author of The Queer Child, which Young refers in her thesis – to believe that there is something queer about "the child.”

"This is not necessarily linked to LGBTQI+ identity but is something more broad, in that they break the norms of gender and sexuality.”

According to Young, adults can be concerned by children behaving too much like an adult, and vice versa: adults behaving too "childishly," or adults who want to remain being a child.

The killer child often interferes with the idea of development and the transition from child to adult, Young says.

"Several of the children in the five books behave precociously or refuse to grow up.”

Killer children break gender norms

The murderous children break norms when it comes to gender.

"They are either hyper-conformist or have a gender expression that completely breaks gender norms," says Young.

Young also noticed that, in certain parts of the stories, the children don't appear very heterosexual:

"It's either a form of asexuality that lasts beyond their teenage years, or it seems the children have repressed or withheld some form of sexual desire.”

In the book The Wasp Factory, the killer child is a boy who later finds out that he was born a girl. Other murderous children are distinguished by being sexually uninhibited, such as the title character in the book We Need to Talk about Kevin.

"Kevin wears tight-fitting clothes to accentuate his physique, and it seems he uses his sexuality as a weapon," Young said.

"For example, the mother recounts an episode in which Kevin and his classmate accuse a female teacher of sexually harassing or making advances on them.”

When children misbehave, it has often been common to blame their mothers.

Kevin's relationship with his mother is also sexually charged.

"When Kevin becomes a teenager, he masturbates with the door open so that his mother can see.”

Mothers

The example above alludes to a recurring theme in the literature about murderous children: it is often the mother or the female head of the family who suffers.

After Kevin carries out a massacre at his school, gunning down several of his fellow students and teachers, his mother ultimately becomes a social pariah.

"When children misbehave, it has often been common to blame their mothers," Young explains.

Although there is now a greater focus on fathers, it was previously the women's responsibility to raise children, she points out. Moreover, the biological connection between mother and child also influences the narratives:

"If we look at cultural understandings of why someone is born evil or demonic, there has often been a focus on pregnancy and that the evil is something that arose during pregnancy.”

Young points out that this explanation is most common in supernatural books.

While a lot of terrible things happen to the mothers in the books she's studied, Young does not believe that the authors use the misfortune of women to set an example.

"If anything, they thematise a societal tendency.”

Who gets to remain innocent?

Another theme that Young explores in her thesis is how the notion of childlike innocence is used to maintain heteronormative, patriarchal, and racist structures.

It takes a lot of effort to maintain innocence. When it comes to gender, Young believes that much of the responsibility for preserving the children's innocence has fallen to the mothers, who put a lot of time and effort into shielding their children from the world and protecting the family idyll.

According to Young, race and class play an important role, to the extent that it takes social and economic resources to maintain the innocence of children.

"It’s easy to imagine our notion of a 'child' is universal, although that’s not the case. Not all children enjoy the kind of protection and praise that we give children.”

Young does not consider it a coincidence that all the children in the five stories are middleclass white kids.

"In some way, I think these stories play with that ideal. These literary works are exciting and groundbreaking because they portray the most idealised children as dangerous.”

Anything perceived as potentially harmful to children tends to be supressed, ignored, or demonised in society.

The killer children experience neither poverty nor racism. In other words, it's not their circumstances that drive them to commit these terrible acts – it's something innate.

Children become ideological weapons

The idea of childlike innocence is problematic because it is often used to define what constitutes desirable behaviour — even for adults.

"In my thesis, I reference a queer theorist named Lee Edelman who wrote a book called No Future. In the book, he discusses children as a cultural symbol and how children are used discursively to influence or control what adults can say and do.”

According to Edelman, the child is constructed as an idealised future citizen who must be protected and cared for.

"Thus, things that are perceived as potentially harmful to the child tend to be suppressed, ignored or demonised in society.”

As an example, Young points to the ongoing discussion around children, gender expression and sexuality.

"There's a lot of focus on what's acceptable for children to see. Are drag shows dangerous for kids? Should children learn about different gender identities at school? Nowadays, there are clearly strong opinions about gender and sexuality, and many people look towards children.”

"It’s like a battleground for something that might really be more about adults.”

Queerness, moralism and the monstrous

Lars Rune Waage is Head of Department and Associate Professor of Literature Didactics at the University of Stavanger and author of the 2009 book “Skrekkens grenser: seksualitet og tekstualitet i Sigurd Mathiesens forfatterskap” (the boundaries of horror: sexuality and textuality in Sigurd Mathiesen's literary works).

He recognises the tendency of authors to use gender and sexuality to build moral authority or characters as baddies.

In Sigurd Mathiesen's Blodtirsdagen (Blood Tuesday) from 1903, which Waage has studied, the young protagonist feels a strong erotic and sexual attraction towards another boy.

"It ends with a whole group of boys being killed, and afterwards the two commit suicide – with a knife.”

"These are quite strong themes, and one discussion it invokes is how contemporaries viewed 'sexual deviance' as an illness and perversion. The homoerotic often turns into violence,” and he adds:

“This is perhaps an expression of self-censorship on the part of the author when depicting this forbidden eroticism.”

In other words, queer literature acts as an outlet, and – like the stories about killer children in Young's studies – uses narrative form to emphasise a moral point.

Waage has also studied monsters in children's literature.

"We probably like monsters because we tolerate and sometimes enjoy being frightened – in a slightly controlled way.”

"The monsters also look like us. They have human qualities – and by recognising something human in them, they perhaps become even more frightening.”

A longer version of this article was first published in Norwegian