The painter Nikolai Astrup was a collector and a very systematic person. Among other things, he collected drawings and sketches from his childhood and adolescence in a scrapbook that he himself called Gutteboken ("The Boy's Book").

This book was exhibited at Kode in 2016, at the same time as art historian Kesia Eidesen Halvorsrud started working there. She was fascinated by the book, and it became the point of departure for her doctoral thesis Gutteboken som kompositum. En studie av Nikolai Astrups barne- og ungdomstegninger (The Boy's Book as a compound. A study of Nikolai Astrup's drawings from childhood and adolescence). Here she found perspectives that shed new light on Astrup's oeuvre.

"This is complicated material. Gutteboken is a scrapbook with almost 900 drawings, figures and scraps of paper put together in a special way," Halvorsrud explains.

"I wanted to investigate what kind of contexts it can be placed in. Eventually, I found that relating it to the notion of home was what opened the most doors. In the past, the artist's drawings from childhood and adolescence have typically been seen in light of the genius artist's inner life, but in light of the home, other interesting perspectives emerged. It was a process of recovery: Gradually, I saw that Astrup came from a creative home that influenced him."

Mythologised in art history

Halvorsrud says that she became aware that Nikolai Astrup's life has largely been mythologised in art history. Not much research has been done on him, and the classic biographical account tells the story of a young man who became an artist against all odds, with his conservative father, a minister, as his polar opposite. Halvorsrud wants to provide more nuance to this impression.

In particular, she highlights the influence of Astrup's mother, Petra Astrup, who was a central figure in the handicraft movement.

"There was a striking gap in the biographical literature," says Halvorsrud.

"Petra Astrup is actually only mentioned in one sentence in the main biography on Astrup. There, she is introduced as "his father's wife", while his father is portrayed as playing a major role in the dramaturgy about Astrup’s struggle to become an artist. However, there were many people in Astrup's network who had an important contributing impact on him."

"I am critical of the narrative that places the father at the top and the child at the bottom of a hierarchy. Deleuze and Guattari have criticised such a mindset in their works, and their critique of family structure in psychoanalysis became an eye-opener for me."

Astrup's mother was not the only female artist to be passed over in his biography. His wife, textile artist Engel Astrup, who exhibited embroidery and was on the board of the local branch of the Norwegian Folk Art and Craft Association in Jølster, is also largely overlooked.

"The great Astrup biography is from 1986, and it is perhaps not to be expected that his mother and her handicraft would be given a significant role in it. But if you take a closer look at how other women in the artist's social circle and support network are described, a pattern emerges," says Halvorsrud.

"Engel Astrup as an artist is also overlooked in the earlier biographical account. Her creative practice is not mentioned, although the biographer must certainly have been aware of it. There seems to be something about the structure of the artist biography as a genre that excludes important supporters in the artist's life."

Neglected handicrafts

Halvorsrud decided to find out what sources existed. At the National Library she found digitised articles from local newspapers and printed matter from industrial exhibitions around the country. In this material she found several traces of Astrup's mother.

Petra Astrup was a weaver and showed her work at industrial exhibitions. Here she received good reviews and won prizes for her handicraft. She had her own weaving workshop on the family's farm, and also employed other weavers.

"Traditionally, there has been little talk about the importance of handicraft in art history," says Halvorsrud.

"I realised how important the handicraft movement was as an institutional network, a fact art history often fails to highlight. There is often a hierarchical view of art forms, and the handicrafts have long been overlooked. Many art historians have probably had a more narrow view of what visual art actually is and what is worth writing about."

Halvorsrud's impression is that cultural history has had a greater understanding of the importance of institutions such as the Norwegian Folk Art and Craft Association. She therefore benefited from theory and methods from cultural history in her work.

She says that it has been a long struggle to raise handicraft's status to the level it enjoys today. Many still see it as a minority among artistic expressions. At the same time, handicrafts have been a source of income for several families and allowed Petra Astrup, among others, to pay for her sons' education. Only a generation earlier, women were not allowed to make anything for the purpose of selling it.

"But households in rural areas relied on bartering, and not just on a monetary economy," says Halvorsrud.

Working in the home on a large farm did not have much monetary value, but a great deal of work went into producing food and clothing and objects made for the home, or to be bartered or sold. Traditional women's work is therefore often not included in economic history or the history of domestic industry, because it has not necessarily contributed to the visible monetary economy," Halvorsrud explains.

"This makes it difficult to see the important contributions women have made," she says.

"The word economy comes from 'oikos', which means home. In the past, people probably had a more holistic idea of what it meant to contribute to the running of a home and a farm."

Learned from the Norwegian Folk Art and Craft Association

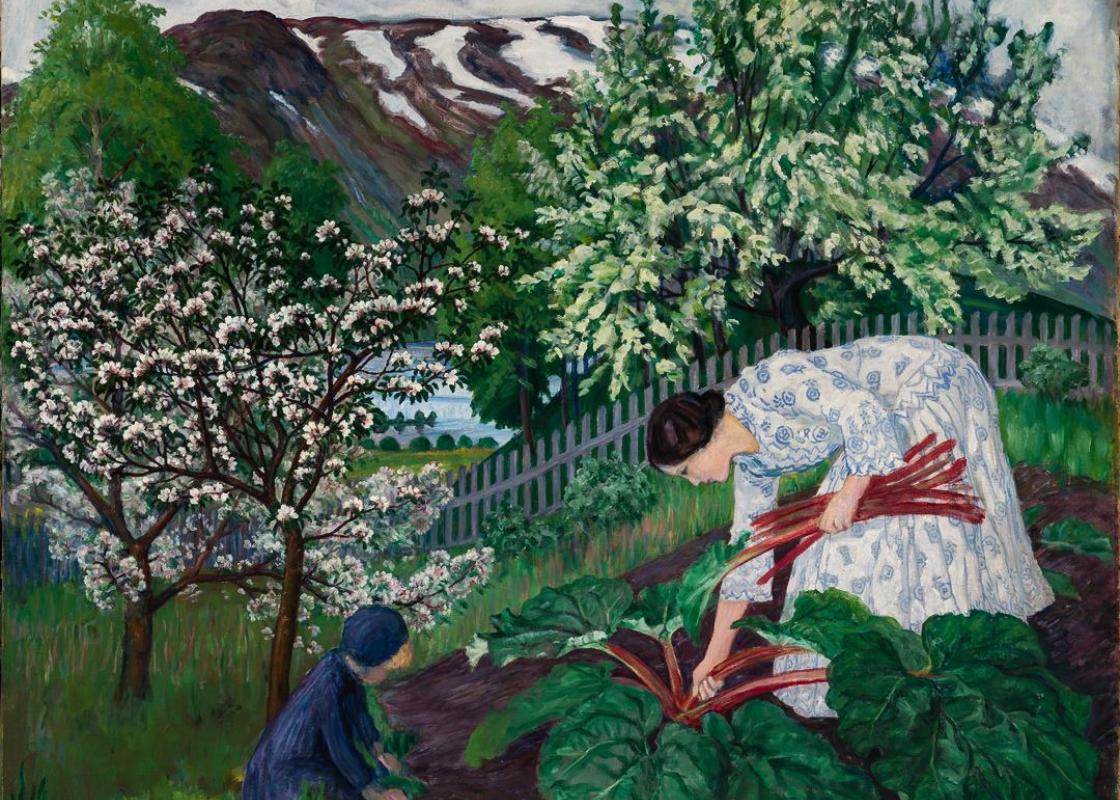

According to Halvorsrud, the Norwegian Folk Art and Craft Association also had a major influence on Nikolai Astrup's oeuvre. He collaborated with his mother and made several of the patterns for her weaves. It has been known that Astrup drew patterns for weaves, but the importance of handicraft and his mother's practice has previously received little attention in the literature written about him.

"A good example is when Petra Astrup exhibited weaves and other textiles in Trondheim in 1902," says Halvorsrud.

"The pamphlet from the exhibition states that the weaves are made with patterns by 'the weaver's son, the painter Nikolai Astrup'. She may have had a say in this reference to her son, as this is a full three years before his debut exhibition. She included him in her own practice. That’s why I see Nikolai Astrup's mother Petra Astrup as his first teacher."

The so-called feminine artistic expressions have been underestimated by history's selection mechanisms.

"Nikolai Astrup also exhibited his work alongside his mother's at the 1914 Jubilee Exhibition in Kristiania, a very famous exhibition in Norwegian art history. But until now, no one knew that his mother exhibited six huge tapestries designed by her son at the same venue."

Their cooperation goes back to Astrup's childhood. The Astrup family lived in a vicarage in the country, where they dyed wool with plants and used it in the weaves. This work required the collaborative efforts of many people, including the children, and Halvorsrud points out how this must have affected a young Nikolai Astrup.

"An understanding of colour and practical knowledge of art forms is something he brought with him from home," she says.

"Astrup had a very diverse practice, and handicraft is part of it. It's interesting to look at in Gutteboken, where he has included small sketches of patterns for weaves. But handicraft products are utility objects that are subjected to wear and tear, and pattern drawings are not assigned the same value as the artist's signed drawings. Unfortunately, much has been lost."

A gendered myth

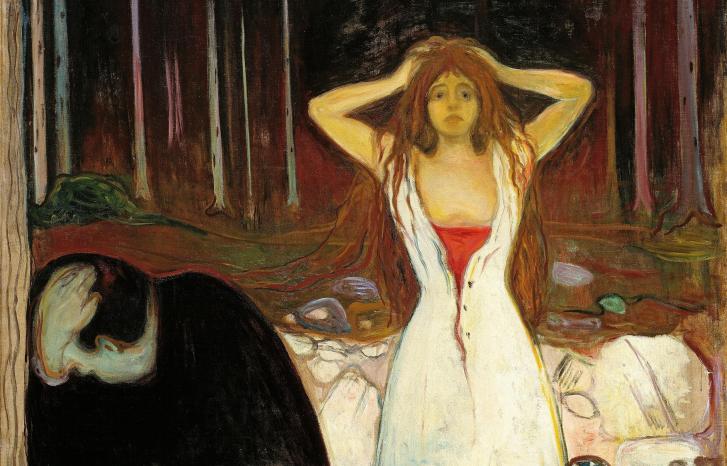

Lars Toft-Eriksen is an art historian and curator at the Munch Museum. He has written his doctoral thesis on the artist myth surrounding Edvard Munch and sees several similarities in how such myths have been created throughout history.

"The modern artist myth is largely linked to the ideals of the Age of Enlightenment and the Romantic movement of the 18th and 19th centuries," says Toft-Eriksen.

"Then, visual artists were regarded as intellectual workers, where they had previously been seen as craftsmen. This is closely linked to this period's emphasis on originality and genius. The visual arts thus moved away from the guilds and into the intellectual realm, together with writers. People began to see the artist as a gateway to something bigger, whether it was our inner, spiritual being or the divine. A notion that to a large extent lives right up to our time."

In Nikolai Astrup's case, the artist myth has also played on the idea of him as an outsider.

"The family background that Halvorsrud highlights shifts that perspective," says Toft-Eriksen.

"But it has been an important myth. The artist as an outsider becomes a mirror image of modern, bourgeois individuals and can give them an idea of themselves. Freedom was and still is an ideal of the bourgeoisie, and the outsider becomes emblematic of this."

The artist myth also has a clear gender perspective. Toft-Eriksen highlights how artistic insight has been linked to men, while it is also a gender-transcending category since inner life has traditionally been seen as something inherently feminine. While the visual arts were elevated to the intellectual world, artistic expressions such as weaving and embroidery remained in the craft category.

"This is a topical debate, even today," says Toft-Eriksen.

"The so-called feminine artistic expressions have been underestimated by history's selection mechanisms. They have been written out of art history, partly because they do not fit with the traditional artist myth and the aesthetic hierarchies."

He believes it is important to both understand and challenge the myths. By taking a critical approach to the narratives that form the basis of art history, one can see that many of the myths are not realities. At the same time, their influence continues."

"It's a demanding craft where you're at the mercy of the sources you can find," says Toft-Eriksen.

"In recent decades, we have seen art historical research that challenges myths and conventional selection criteria. But that doesn't mean that the myths are necessarily weakened, because many of them are strongly rooted in cultural, social and legal structures. Among other things, they have laid the foundation for important financial conditions for artists, such as legislation on intellectual property and copyright. It builds directly on the myth of the artist as an original genius."

A patchwork of expressions

Nikolai Astrup had a broad interest in traditional artistic expressions. He was involved in folk music, folk dancing and contributed to the work on the Sunnfjord version of the national costume, or bunad. He had an immense interest in textile work, and he was instrumental in creating an open-air museum in Førde, where textiles and antiques were collected.

"He was an artist with many interests besides painting, says Halvorsrud.

Compared to many other male artists from the same period, Astrup appears to have been quite the feminist.

"Gutteboken provides an insight into the non-hierarchical aspects of his art. Astrup didn't value any art forms higher than others. From childhood, he was used to socialising with and learning from very competent women, and he was part of a broad-ranging collection culture. I see it as a patchwork of expressions, where no art form is placed above another."

According to Halvorsrud, it is not appropriate to treat the contents of Gutteboken as sketches for future works of art, as they have often been in the past. Her thesis is the first major work to look at Astrup's drawings, and she argues that the book has intrinsic value as an independent work.

"If we look at interaction and connections between the different art forms in Astrup's life, we can challenge the myth that the artist stands all alone and does everything on his own," she says.

New perspectives

Nikolai Astrup himself seemed to appreciate the people supporting him. In his correspondence and notes, it appears that he had a close relationship with his wife and that he saw her as a partner.

"I have worked as an art historian for many years, and compared to many other male artists from the same period, Astrup appears to have been quite the feminist," says Halvorsrud.

"The way he describes women is markedly respectful. He also mentions several female artists he admires, such as Kitty Kielland and Frøydis Haavardsholm. In his letters he mentions several female artists who are unknown today, including Eva Sartz, who, interestingly enough, exhibited her own childhood drawings."

Halvorsrud believes it is important to take a critical approach when encountering older artist biographies. Art historians must dig deep into the archives and engage in relevant discussions in the discipline to find new, relevant perspectives. This way, we can find stories that have previously been overlooked.

"I think you can find a lot of new things with an approach like this," she concludes.

"There has been more emphasis on highlighting women in recent years, and there's a lot to find if you look at it through that lens. There are so many artists who have had a support system around them of talented, competent people, like their wives and mothers. I'm sure there are many other examples of the same."

A longer version of this article was first published in Norwegian