In a new PhD thesis, gender researcher Gilda Seddighi studies public expressions of grief in the social media in Iran following the riots in 2009, and looks at how these expressions reflect gender norms and norms of sexuality.

In particular, she has analysed three Iranian Facebook pages dedicated to dead or incarcerated Iranians. She discusses these pages in light of the term ‘grievable lives’ – which lives are worthy of grief – and what may be characterised as political actions.

“In 2008 I went to Iran in order to gather information for my master’s thesis about the Iranian feminist movement. I was interested in how gender equality was perceived in Iran internally within the feminist political networks,” she says.

Network based feminist movement

According to Seddighi, the Iranian feminist movement is now network based. It distinguishes itself from previous feminist movements precisely by building networks with other movements, by trying to include these in their own activities, and by being a common platform for all.

“For instance, many young men from the student movement are active in these networks.”

In 2009, shortly after Seddighi had submitted her master’s thesis, massive demonstrations broke out following the presidential election, protesting against rumours of election fraud and demanding democratic reforms. The revolt came to be known as the Iranian ‘green movement’.

Seddighi was interested in how the revolt might affect the feminist movement.

“People discussed whether the feminist movement should take part in the revolt or not,” she says.

“The feminist organisations did not participate in the revolution in 1979, and some people thought they hadn’t been sufficiently active in their work to challenge perceptions of gender during the revolution. Much of the progress they had seen for women before 1979 was lost after the revolution. Before the revolution, Iran had a number of women-friendly regulations that were subsequently changed. Some people thought that this was partly because feminists didn’t participate in the revolt.”

In 2009, however, many women activists took part in the protests.

“An important part of the revolt was to create new identities, new ‘grievable lives’ that might represent the face of the revolt,” says Seddighi.

She states that the social movement that drove forth the revolt was not an homogenous movement: it had no formal leaders or organisation and tried to work based on both online and offline networks in Iran and abroad.

“I followed many groups on social media during and after the revolt, and looked at how the groups’ public faces changed over time: Which identities were considered worthy or ‘grievable’, and who were involved in creating these faces or this representation?”

The green movement

Seddighi began her work on her doctoral thesis in 2011, but already from 2009 and 2010, she had followed how the green movement created their identity. However, a lot had changed in only two years.

“In 2009, the revolts were spontaneous, not organised. In 2010, there were some attempts at forming organisations from the revolts. Such activism was heavily attacked by the authorities, and many journalists fled into exile or were arrested during this period. In 2011, the symbolic leaders of the green movement were arrested, and they are still under house arrest.”

Calling someone a martyr and mourning someone who has been characterised as a martyr may be perceived as a political act.

When Seddighi began working on her PhD, there were no longer any activities in the streets. The attempts at forming organisations had been smothered, and there was much internal conflict within the movement.

“There was a lot of depression within the movement in 2011, but in the social media many still tried to speak and act as if it didn’t exist. When someone was arrested it was said that they were part of the movement, and the activism was still alive on Facebook and the social media – but not in the streets.”

Seddighi chose Facebook groups she could follow contemporaneously.

“I wanted to study how norms related to gender and sexuality are produced within Iranian activism in the social media.”

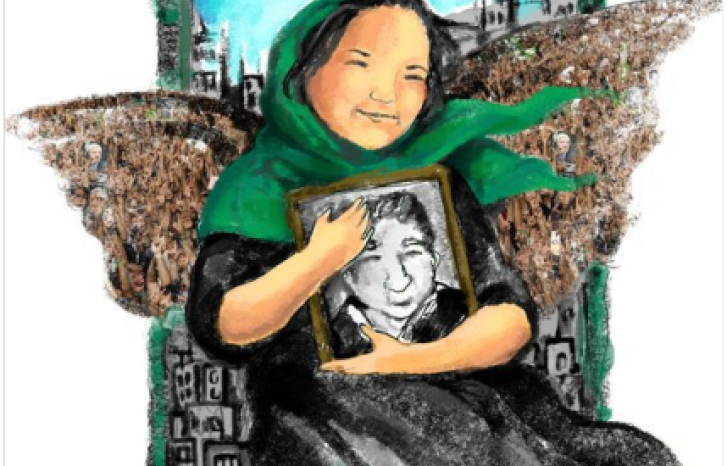

Mothers and martyrs

Of the three Facebook groups Seddighi chose, the first was in memory of a democratic activist who died in her father’s funeral: ‘We are all Haleh Sahabi’. Another was in solidarity with the famous human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, who was arrested and went on hunger strike in prison. She was also the object of an Amnesty International campaign. The third group was established by Iranian asylum seekers in Harstad in Northern Norway in solidarity with grieving mothers: ‘The Supporters of Mourning Mothers of Harstad’.

“Haleh Sahabi was labelled a martyr. Women are rarely characterised as martyrs, so this is very interesting,” says Seddighi.

She says that at the time, suspected rebels were attacked to such an extent that many were afraid to write about ‘martyrs’ on Facebook.

“Calling someone a martyr and mourning someone who has been characterised as a martyr may be perceived as a political act even when it is understood as ‘apolitical’ by the participants themselves,” says Seddighi.

According to her, in Shia Muslim culture the term ‘martyr’ is used particularly in relation to the story about the prophet Mohammad’s grandchild, the imam Hussain. The term is highly politically charged, and according to the researcher, the story of Hussain’s martyrdom is central to political theory within Shia Islam. Individual techniques and rituals have been developed for mourning Hussain’s death: ‘Martyr’ is not just a word; it also refers to a practice that draws attention to a person’s life and death.

Women as political players

“Traditionally, women have played the grieving part, or the part that publicly expresses grief through grief ceremonies,” she says.

“Since 2009, we have seen that more women are mourned publicly as martyrs. This shows that they have become accepted as political players.”

Precisely the question of who are worthy of being mourned, what lives are considered ‘grievable’, has been a central point in Seddighi’s thesis.

“The question was how some people were mourned in public – how their lives were ‘created’ and represented in public as people who deserve the attention. The social movement created an identity through these lives and faces.”

Since 2009, we have seen that more women are mourned publicly as martyrs. This shows that they have become accepted as political players.

The Facebook group for the human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh was, until Sotoudeh was eventually released from prison, run by an Iranian man who had been in Iran during the protests and subsequently escaped to Europe.

“In 2012, many Iranians who had been active in the democratic movement and in civil society fled into exile abroad. Those who continued their activism from abroad largely emphasised human rights in order to create solidarity internally in Iran.”

However, due to the strict censorship and the suppression of activists, many activists were reluctant to show up for interviews with Seddighi.

“I wanted to interview the administrators behind these Facebook pages, but it was very difficult due to all the arrests that were taking place. It could have put my informants in danger if I kept in touch with them.”

The researcher sent out more than a hundred invitations for interviews, but only a few responded. From the first Facebook page, Seddighi only got a response from eleven people. From the other page, she interviewed a total of thirty people.

Play on family affection

The feminist movement was behind an important campaign during the protests in 2009 called ‘Mourning Mothers’. Here, people gathered to publicly mourn those who had been arrested and killed. Seddighi studied activities in solidarity with the mourning mothers on a Facebook page established by Iranian asylum seekers in Norway.

“These groups all played on the Iranian martyr tradition.”

Even the groups who largely leaned on human rights argumentation, such as those supporting incarcerated activists, played on the techniques from the martyr stories, according to Seddighi. For instance through exaggerating the mourning and through references to family affection.

Family affection is highly important in order to draw attention to a person whose life is considered ‘grievable’.

“Family affection is highly important in order to draw attention to a person whose life is considered ‘grievable’,” says the researcher.

“There are many ways to do this. An arrested activist might be presented as a mother who has been taken away from her children, with a husband longing for her: References to family affection are central to representing lives as ‘grievable’.”

In the story of the prophet’s grandchild Hussain’s martyrdom, which is important within the Shia tradition, the sister and other female family members play important parts. This shows that women’s expression of affection is a significant part of the ritual.”

“You have to be able to invoke family affection not only in order to be mourned, but also in order to participate in mourning processes. It enables you to present yourself as a political subject.”

Whether the groups appealed to human rights or martyr stories, grief was largely related to family affection. Family in this connection is used to refer to the conventional family. The grief becomes visible through women’s role in the family, the mother in particular.

While the notion that women may be attributed the role of martyr implies that the gender roles are changing, the references to family affection contribute to the reproduction of the dominating norms for gender and sexuality,” says Seddighi.

Political actions

“For instance, some women have written about their love for their husbands in the social media in order to draw attention to incarcerated men. These are political actions within a heteronormative framework.”

According to Seddighi, these norms contribute to shaping the idea of what is understood as a political action.

“I tried to demonstrate how the changes that have occurred, for instance with women being considered martyrs, have taken place within the same notion of gender roles and norms related to gender.”

In the Mourning Mothers network, the term ‘motherhood’ was expanded to include various social and political groups in the grief practices. Eventually, the network not only included mothers who had lost their children; everybody who wanted to participate were welcome.

“When motherhood was no longer directly relevant in terms of biology, it enabled both men and women with various political backgrounds to act through the notion of motherhood.”

Some nevertheless still struggled to take part in the network and in the idea of motherhood, such as the asylum seekers behind the support group in Harstad. Those who created the network Mourning Mothers had taken for granted that everyone who took part in the transnational movement in the social media were still entitled to citizenship.

“For the asylum seekers, their connection to the nations in which they lived was so uncertain that they struggled to take part in the grieving processes.”

The apolitical is political

Many of the participants in the groups that Seddighi studied in her thesis described the groups as ‘apolitical’.

“In the beginning I didn’t really take it seriously. But eventually I had to find out what they actually meant by it.”

Many described it as dissociating themselves from conventional politics, says Seddighi. ‘Apolitical’ was a way of saying that what they did was not institutionalised or hierarchical, but rather horizontally organised.

“My aim was to politicise the ‘apolitical’ by showing how the creation of ‘grievable lives’ is a political act in itself. In this way they take part in politics.”

Translated by Cathinka Dahl Hambro.

See also: Martyrs on Facebook

Gender researcher Gilda Seddighi recently defended her PhD thesis "Politicization of grievable lives on the Iranian Facebook pages" at University of Bergen.

In her thesis, Seddighi analyses three Facebook pages that concerns themselves with the lives of Iranians who are either dead or in danger of being killed. The pages deal with various aspects of women’s roles such as martyr, human rights activist and grieving mother.