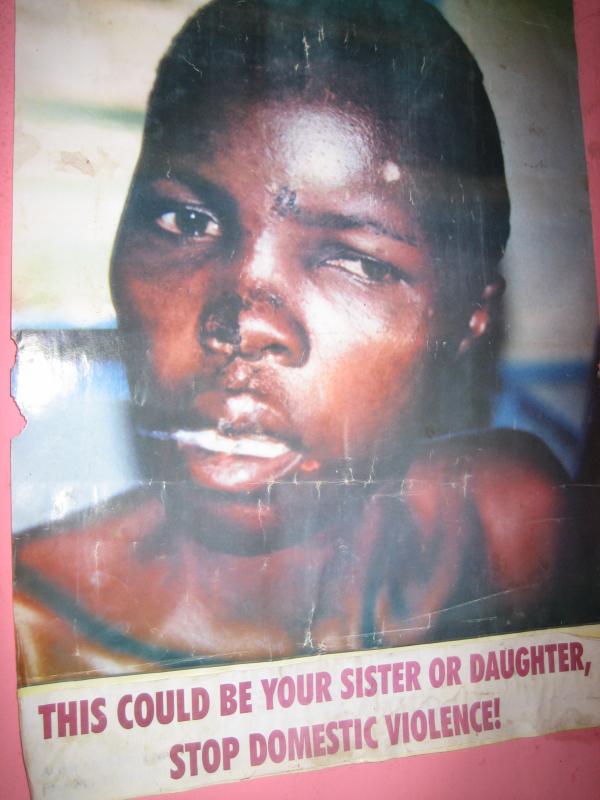

For in the Buduburam refugee camp for Liberian refugees in Ghana, where this woman lives, a raped woman is, as in so many other places, unclean and used, and probably has suspect morals.

- It is a great paradox. We are talking about a community that has experienced mass rape. A large majority of the women have been raped at least once. Even so, sexualized violence is covered by silence. Barely anyone talks about their experiences with rape, says Sæba Bajoghli, who has done fieldwork and interviewed raped women in Buduburam for her Master’s thesis at the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies of Culture at The Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Not so different after all

- It struck me with an incomprehensible strength. All the horrors that these women have experienced. The poverty, the need, and the brutality they related from the war they had experienced were overwhelming, says Bajoghli.

But when the shock had settled, she started to notice similarities with her own society.

- During the process it became more and more clear to me how little Ghana and Norway differ from each other when it comes to this subject. There are some underlying attitudes and understandings about women, men and sexuality that lead to raped women meeting the same hurdles, though possibly to different extents, says Bajoghli.

The similarities are so great that Bajoghli to a large extent has been able to use Nordic gender research on gender power and sexualized violence in her analysis of the conditions in Buruburam.

A real rape?

- Was it really rape? In Norway, NOVA-researchers Kari Stefansen and Ingrid Smette have shown that victims of sexual assault have difficulties defining that they have been subject to rape, unless it concerns assault, the assailant was a stranger and the victims are randomly chosen. The myth of what a “real” rape is stands strong in Buduburam, says Bajoghli.

A “real” rape is committed by a stranger and leaves injuries or marks on the woman’s body. And there are legitimate and illegitimate victims of rape: if the woman has done anything that can be thought of as encouraging him, by choice of clothes or flirting, it isn’t really rape.

Bajoghli tells about an informant who, in the middle of the interview, went home to gather evidence: bloody panties and a board with two nails sticking out, the weapon the rapist used against her.

- That was how she wanted to convince me that she really was raped, despite the fact that I made it clear that I believed her. I had after all requested to speak with her because she was raped. It seems as though the women are used to working hard at being believed. This is probably something many Norwegian rape victims also experience. It is often word against word.

Stigma

Bajoghli frequently experienced that the women themselves actively contributed to the stigmatization of raped women.

- There are some deep rooted understandings that the women seem to be trapped in. It confounds me that these live on in a society where so many have experienced sexualized violence.

The condemnation of rape victims often came from women who had themselves experienced rape.

- For many this is about distancing themselves from “the bad women” so as to increase the likelihood that they are legitimate victims, says Bajoghli. And regardless of if a person has any guilt, a rape takes away that person’s dignity, as this 25 year-old woman describes:

“I do not want for anyone to know about it. They will keep mum, say that they feel sorry for me, but behind my back, in their homes, they will talk about me. And if there are any misunderstandings between us, they will bring it up: Oh, they raped you! What do you have to say? After all, you were raped. You know, things that will make you feel bad… I cannot tell it to anyone.”

Innocent, yet unworthy

The ruling train of thought in Buduburam makes women responsible for avoiding sexualized violence. If they do not succeed in protecting themselves, many feel that they can basically blame themselves. Bajoghli calls this the self-infliction discourse, and she recognizes this from her own society. - Even though the self-infliction discourse is stronger and less veiled in Ghana, I recognize the train of thought in Norway. Also here women are made responsible to avoid rape: we are recommended to take taxis home from town and to avoid dangerous situations.

Some of the Liberian women had been raped by soldiers or rebels in connection with the conflict in their homeland. These wartime rapes are less understood as self-inflicted than other rapes. But the stigma of being used and unclean is one the wartime-raped women must also live with.

One of Bajoghli’s informants was group-raped while her fiancé watched. She tells with pride and gratitude of how he stayed with her, in spite of his friends who encouraged him to leave her. The pastor of the congregation managed to convince the fiancé that the raped woman cannot be blamed. That he lets himself be convinced and stays with a “used woman” makes him a hero in the raped woman’s story.

Work toward change

- But the self-infliction discourse remains strong, even in the assistance programs, says Bajoghli. - It becomes quite apparent after a while that we always talk exclusively about women when fighting sexualized violence. The men’s role and actions are essentially taken for granted. In Buduburam they get away with little repercussion.

The common understanding of men’s sexuality in Buduburam is that they simply can’t control themselves if they are sexually attracted to a woman. A highly sexualized culture, where young women show their bodies and flirt at bars, thus becomes an explanation for why rape is so widespread, even among those who are supposed to help the women.

Men’s power and powerlessness

Bajoghli on her side believes that sexualized violence is connected to a displaced power-relationship between the genders, partly as a result of the refugee situation.

The women are active and interfering, earn money and raise the kids. In the camp there were also several female high tier leaders. Overall, the men manage themselves worse and experience that they are losing power. The extensive violence, particularly within relationships, can be interpreted as an attempt at regaining what was lost.

Bajoghli bases this analysis on ideas of the American researcher Robert Morell, who claims that African men have lost so much power in most arenas that they compensate by reining in the sexual control of women.

Talking point politics

In the last few years violence against women has received a higher placement on the international development agenda, not least in connection with UN resolution 1325 on women, peace, and security. Bajoghli is pleased with the increased attention, but fears talking point politics.

- “Violence against women” becomes a kind of catchphrase, thrown about to gather resources. The work that really is done to take care of the women and fighting the violence is frighteningly inadequate and in part poorly organized. Several women I met said they had taken courses and learned that rape is not the women’s fault, but later in the interview they argue that it is her fault nonetheless. It does not help to arrange one course now and then; they need more of a long-term view in this work.

Liberia

- Was founded by liberated African slaves

- The first sovereign African republic in 1847

- Civil war broke out in 1989, when guerrilla leader Charles Taylor rebelled against President Samuel Doe. The civil war lasted until August 2003. During the war the inhabitants were subject to grotesque assaults. Plunder, torture, forced recruitment and sexualized violence was widespread, and forced large parts of the population to flee. Today many Liberians still lives as refugees in neighbouring countries, or as internal refugees in Liberia.

Buduburam refugee camp in Ghana

- Established in 1990 due to the great number of refugees from Liberia

- Run by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- 42.000 refugees. Most of these are from Liberia, but some are also from Sierra Leone and the Côte d'Ivoire

Source: UNHCR Ghana