Back to the library at Sunndalsøra: – I knew that Toril Moi was the Norwegian researcher of gender and literature who really had an international career, says Rekdal. – I had an idea: Was it possible to do a literature thesis, not about a novel, but on a theoretical text? On something Toril Moi had written? It was possible, but it wasn’t easy.

Theory on Theory

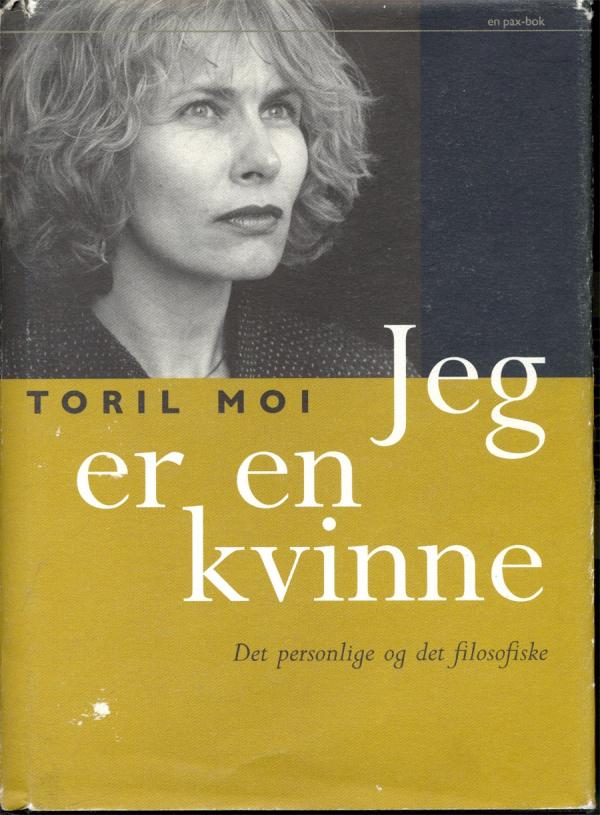

Elin Rekdal would use the analytical tools from literature studies on a theoretical text written by a literary theorist. – I started from the idea that a scholarly text is a creative, written text. In a theoretical book, just as in a novel or short story, there is a form of narrative that is communicated, says Rekdal. She chose “I am a woman” from the book “What is a Woman? and other essays”, that was published in 1999.

– I wanted to investigate how Moi writes theory in this text, Rekdal explains. – For even though this is an academic text, it presents a narrative of a theory.

Moi communicates through autobiographical narratives, personal reflections and purely theoretical explanations. And Rekdal studies her use of literary and rhetorical devices: textual pictures, language, style and narrative voice. Additionally, she investigates the essay’s external relationships, or in other words citations and references to other texts, especially the frequent use of Simone de Beauvoir’s “The Second Sex” (1948).

Rekdal is interested in the fact that there is not necessarily a direct route from the author’s intention to the text. – Toril Moi’s texts have their own voice, and she often refers to her own life. Nevertheless the narrator in the text should not be connected directly to the author of the text. This is because separating the two creates new possibilities for bringing in a more discursive attitude to the text, in Rekdal’s opinion.

– To a certain degree you escape the limitations that exist about what cannot be said about Moi, because I do not know what is the truth. You gain a little more power over the text, and it becomes possible show different layers. It makes it possible to demonstrate things that the author herself has not noticed. It creates room for criticism.

That makes it exciting

In “I am a Woman” Toril Moi discusses whether and how, as a woman, she can write about theory in a way that doesn’t alienate herself and others, and that is not a construct within the patriarchy. Moi argues against a text written by another female literary theorist in which she expresses the belief that the solution is to completely avoid writing theory.

Moi argues for combining the personal and the theoretical, and to do this within the text. – A rhetorical strategy Moi utilizes is to establish a strong self-conscious subject right from the start, through the narrator of the text. In this way she establishes contact and intimacy with the reader. The narratives about personal experiences make this a story one can believe. Moreover, the intimacy with Simone de Beauvoir’s texts, combined with an intimacy based on identification between the narrator and de Beauvoir, function almost as a shield against possible opponents, says Rekdal.

– But, she emphasizes, both what I am doing now in my thesis, and what I did in my master dissertation are my analyses, my literary theory texts. They represent one way of looking at it. As a literary theorist it is my ambition to open the text up, and to present my understanding of it in as convincing a way as possible – to get others to look at the text in new ways. My text will hopefully be just as interesting as the text I am writing about. That makes it exciting.

Oil and Ball etiquette

So far, Rekdal and Moi: Hereafter this text will be about Elin Rekdal herself. She was born in the Norwegian city of Trondheim, two decades after Moi, in 1972. The nineteen seventies was the decade that saw many campaigns to get young women to break with tradition and choose the unfamiliar; A message Elin Rekdal became thoroughly exposed to. – I wasn’t especially politically conscious, and I did not focus upon gender in particular, but the message that “girls can and will” and that we should want to study the natural sciences, took root, she says. So I took natural sciences at sixth form college (Am. High School). – I thought it was cool, because I didn’t want the boys to gain an advantage, she says. She intended to be an oil engineer.

But first she spent one year at college in the State of Illinois in the USA, with a scholarship from the Norway–America Association. Physics, chemistry and maths were replaced by art history, music, textile design and Women’s Studies. – I had no idea that a subject like Women’s Studies existed, says Rekdal. In the course of one year I learned about female circumcision, forced marriage and double discrimination in multicultural USA. American college represented for me a first meeting with gender research, but also rigid rules for how boys and girls should behave. That a woman should, for example, expect a man to open a car door for her, and that he should invite her to the home coming ball. If he didn’t invite her then she should stay home.

– I thought that the American girls were living only an illusion of equality, in that they let men open car doors for them, pay the restaurant bill and invite them to the ball. That system obviously had created an expectation of reciprocation, and it appeared old-fashioned. I felt that there was an imbalance between much that was modern in American society and their views on gender roles – which were both traditional and rigid, Rekdal points out. Together with her fellow Scandinavian students she rebelled against the prevailing ball etiquette: Danes, Swedes and Norwegians went to the ball together – not in pairs, but as a group.

From sense to another type of sense

After what she describes as a year off in the USA, Elin Rekdal came back to Trondheim. She would realize her aim to become an oil engineer. Her application to the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) was sent, and she was accepted. However, only a few days before semester start she changed her mind. For her there would be no NTNU, oil and the North Sea. – I only knew that it would be completely wrong. Of course I liked maths, chemistry and physics; they were fun! But in the course of my year out I had discovered other subjects, subjects that challenged me intellectually in other ways, says Rekdal, and adds: – Yet, these weren’t the words I used then. It was more to do with that I would stop making “sensible” choices, and would rather think more closely about what I actually wanted to do.

When you want to think about what you actually want to do, examen philosophicum (the introductory semester of a Norwegian university education) is a good choice. While she was studying, Rekdal worked with assistive devices for the blind and visually impaired. Afterwards, she took Social Anthropology. She quickly understood that she did not fit in there. In a desperate hunt for something that suited me I tried literature.

– I am a literary person who has always both read and written a great deal, says Rekdal. – To have world literature on the reading list was pure luxury for me. Moreover, I like analysis - to think around a text. Early on I read about psychoanalysis, and I am interested in interpretation and hermeneutics. Even though much literary theory can be rather abstract, inaccessible and verging on philosophy, I like it too. It appeals to me to think on a higher level.

A student was in the process of finding her niche in the academic world. Though she didn’t quite realize it.

Because she was so pretty

It was probably Women’s Studies and Illinois that was responsible: The novice undergraduate student started looking through the reading list for literature with a woman’s perspective, and found – almost nothing. So when the students themselves could choose she went for Virginia Woolf and To The Lighthouse. Nevertheless, it wasn’t this that made the greatest impression on her in her year studying literature. It was the lecture on structuralism. – We had got to Julia Kristeva and her theories, and the first thing the male lecturer said was as follows: “There’s no hiding the fact that she did so well in the linguistic milieu in Paris because she was so pretty”. He most probably just expressed himself in a clumsy fashion. However, what is sad is that there are numerous students that remember Julia Kristeva because “she was so pretty”. And Kristeva was the only woman among all the theorists we studied, Rekdal says.

Rekdal moved on to art history, in Bergen, and a distance learning course in feminist literature theory in Trondheim. I did my undergraduate thesis on feminist post-structuralism and art. – And within post-structuralism it’s possible to ask questions about both the production of meanings and power as universal and singular entities, and other terms that are thought of as natural, absolute and ahistorical. Gender, for example, she says.

Feminist theory and the ground

Aren’t literary theory and art history very theoretical, purely interested in the text or the work of art and not the society they are a part of? – In Norwegian literary theory there has been in the last decade a strong tendency look at the text as a reality in its own right, without that necessarily being connected to the world and the society that it’s a part of. Contextualisation has not been a part of Norwegian literary theory in recent decades. Moi is one person who takes a chance, explains Rekdal. In her opinion the need to free a text from the society it was released into arose as a reaction against looking at the text as a mirror of the author’s mind and time. – One could say that literary theory, once in a while, shifts towards the opposite extreme. A text is always written in a society, in a time and by a person. What saved me from disappearing into a context-free tradition of analysis was my interest in feminist theory. It is grounded in a political reality – with feminist theory as one’s tool it’s difficult to lose the context, she underlines.

Transition from book anlysis to book sales

So, she did her masters thesis on Moi. It was possible, but not without a fight. – I had a supervisor who I replaced, because he did not take my project seriously, she says.

Maybe it was the exhaustive process of getting acknowledgement for using feminist theory? Because after having finished her masters thesis Rekdal decided not to remain in academia. She first moved to working in a bookshop, then into publishing, and became a marketing and information consultant for Tiden Norsk Forlag, a Norwegian publishing house. For two years she worked at getting us to buy books, not by analysing texts and inviting us into them, but by getting newspapers and magazines to cover the publisher’s releases. In the course of that time she decided to return to academia. On her second attempt she got lucky with her doctorate application.

Her work with her doctoral thesis is part of the project “When heteronormativity needs to explain itself” at NTNU (The Norwegian University of Science and Technology), financed by the gender research programme of the Norwegian Research Council.

Power

Toril Moi, the internationally renowned professor, now finds herself being closely examined by a twenty year younger research fellow. And so the question: how does one approach an authority like Moi?

Rekdal is aware that her method of reading Moi gives her a certain power. When you put rhetoric and language under the spotlight, you also expose a strategy. – However, there is no point in being critical for the sake of being critical. I wish to be constructive. I would not work with Toril Moi’s texts if I didn’t like them. I am sure there are literary theorists who examine texts that they feel do not touch them personally, but I’m not that kind of literary theorist. You can certainly stick to the ideals of objective knowledge, but it would be wrong not to admit that as a scholar you are influenced by the texts you read, Rekdal observes.

She is not afraid of being influenced, not by Moi’s texts and not by Moi herself. She has recently spent 6 months at Duke University, North Carolina in the USA, the university where Moi works and lectures. For half a year she has attended Moi’s lectures. Rekdal has sat in the auditorium hour after hour, and listened to her pass on her way of seeing and understanding things. Doesn’t this create too much of an intimacy between you and your subject? – I took in what I heard, but also what I saw. I am now back in Norway, and I am concentrating on her texts as theory – without bringing Moi, the person, in, says the research fellow. However, I am always conscious of the problem of intimacy.

Afraid of authority?

Actually, I do see myself as being a little afraid of authority, as a person, Elin Rekdal claims. In relation to the Toril Moi project, however, she has put that anxiety to one side. Both in relation to the person she is studying, and in relation to the academic standards of what is beneficial. – For the point of view of literary theory I have been advised against doing something within feminist theory. The warning is based upon the expectation that I will encounter resistance, that choosing feminist theory was a little “fishy” and not completely accepted. Gender research is established as a discipline in itself, even though it is considered as a little “alternative” to be working within the field. As a researcher of gender you are expected to keep yourself up-to-date with what is happening in your field. However, there is no corresponding expectation for literary theorists to keep themselves oriented to what is happening in feminist theory.

Feminism versus Science

Perhaps what Rekdal describes as “fishy” is partly the impression that feminist theory and gender research are political, and therefore not scientific enough. – Clinging to gender research is the idea that it is the feministic struggle brought into academia, Rekdal says. – However, a fascination for an area of research stems from a personal interest for the questions that are asked in that field, regardless of what position one takes politically. It is naive to believe that academic activity does not contain elements of the personal. Therefore, it is not especially scientific to reject a whole area of research based upon this reasoning.

Elin Rekdal will, in a couple of years, have a PhD, a doctorate, in gender research. This is an exclusive club in this country. – I am wondering if Norway is ready for a Doctor of Gender Research, she says. – When you have a PhD you are potentially an international export, and when I’m in the USA I get carried away by all the possibilities I see there within gender research. At the same time I am very fond of Norway and Europe. When you have been in the USA for a while, you get to the point where you’ve had enough of fast food and double standards.

Translated by Matthew Whiting KILDEN

Elin Rekdal's Master's thesis in literary science is titled Å risikere seg selv gjennom skriften. Fiksjon, diskurs og selvframstilling i Toril Mois teoretiske essay ”I am a Woman”: The Personal and the Philosophical (To risk one's self through writing. Fiction, discourse and self-presentation in Toril Moi's theoretical essay '"I am a Woman": The Personal and the Philosophical') and was submitted to The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Trondheim, Norway in 2001.

The Master's thesis is published on the internet in full in Norwegian - and can be read here:

http://www.hf.ntnu.no/itk/

h_fagsoppg/Rekdal/

Elin Rekdal's Doctoral project Toril Moi: Kjønn og Retorikk i Tekst og Teori (Toril Moi: Gender and rhetoric in text and theory) looks at some central themes in Toril Moi's writing, specifically where she focuses upon gender, body and sexuality. The project aims to investigate how and to what extent Moi's ideas offer new theoretical incites for research on gender and sexuality. Rekdal's approach is to investigate both the themes and structure of selected texts from Moi's output and contrast them with queer theory, and in particular the work of Judith Butler.