– It is possible to create a situation for men where they can participate equally in both arenas, at home and at work. There is little doubt that today’s men want this, he says.

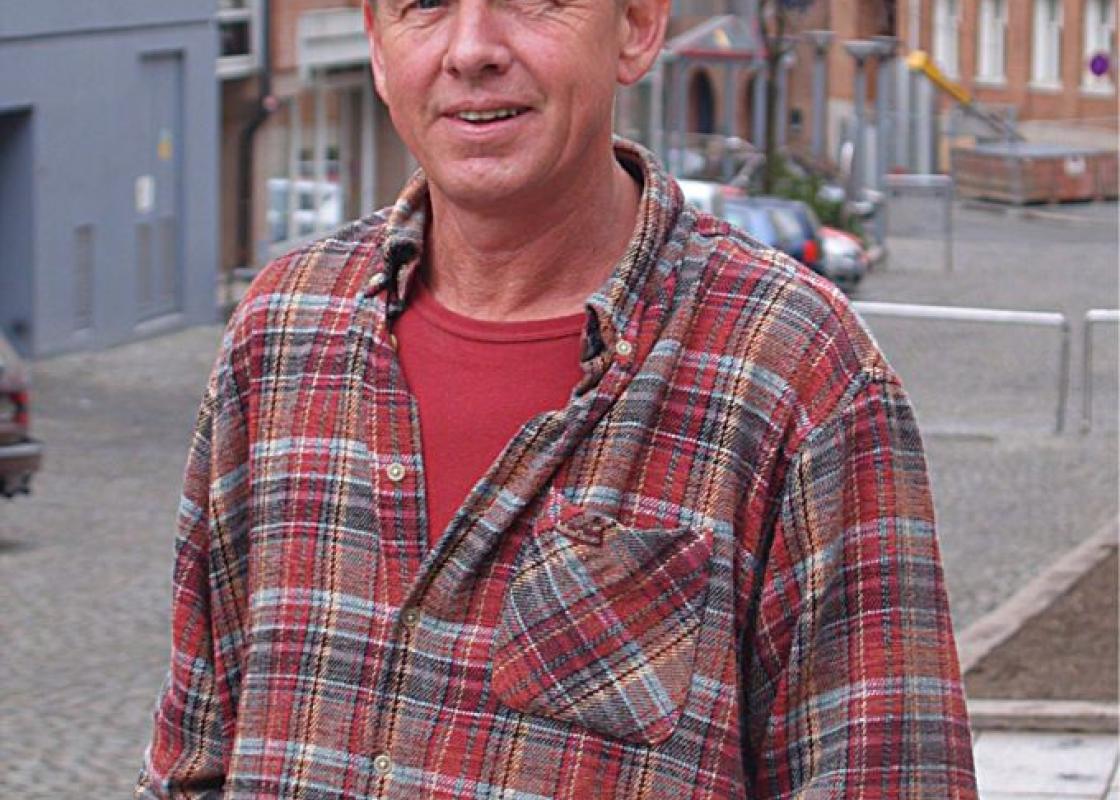

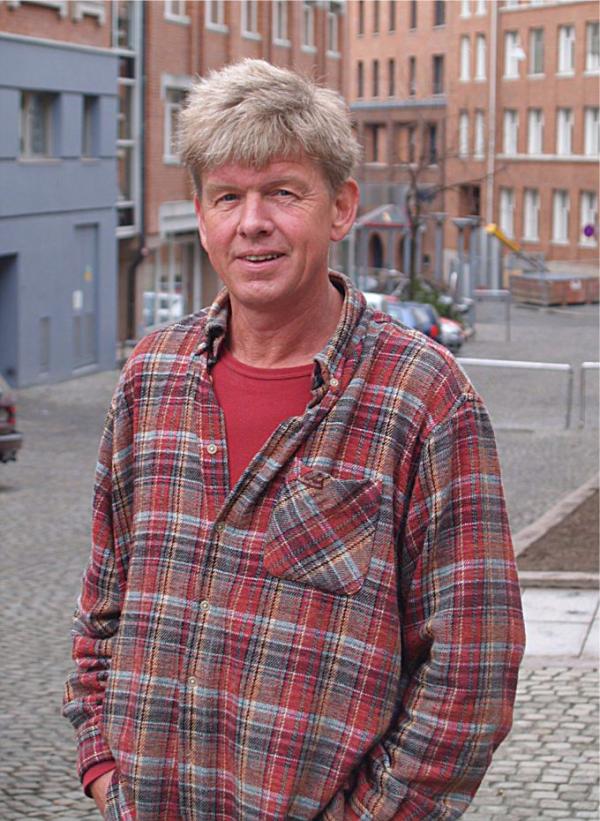

Øystein Gullvåg Holter knows what he’s talking about. For the last three decades he has been researching gender, work, married life and family in Norway. He was doing research in men’s studies before men’s studies was an established field. – The families whose front doors I knock on today are different from those I visited in 1980, he points out.

From principle to practice

He has recently been knocking on doors again for the Nordic survey, “Welfare, Masculinity and Social Innovation”, where 50 men were interviewed in depth. These are men who contribute in the household more than the average man and who are perhaps more interested in being an intimate father. Nevertheless, in Holter’s opinion the tendencies of these men are a sign of extensive changes in society. Changes that can be confirmed to a large degree by an EU study that he is also participating in - “Work changes gender” - in which men over the whole of Europe were interviewed and have answered a questionnaire.

80 per cent of the European men in the selection reject the idea of the father as the main breadwinner. In the opinion of 90 per cent the father should be active and present. – That men would like to contribute more in the home was already clear in the 1980s, but it often only remained a thought. Many men were what Swedish masculinities pioneer, Lars Jalmert, called “in principle men”, says Holter. They have now become better at putting the idea into practice. Time benefit studies in Norway have shown that men carry out 40% of the total household chores, including both housework and childcare. This has increased approximately 10% over the last ten years. – Some people will say that an increase of 10% is nothing special, and that men’s contribution in the home is way too little. Nevertheless, the changes that have taken place from the previous generation amount to a major upheaval in peoples’ daily lives, something that is especially clear when we ask the men to describe how their parents shared the domestic work during their childhood, says Holter.

At the same time women’s share of household income has increased. – In the Nordic interviews we see that the men have become more interested in contributing to their partner’s gaining a good education and a good job. And this isn’t only something happening in the middle classes. Included in the Nordic project is an interview with a Swedish carpenter who commutes to Norway. Why does he commute? First and foremost it’s because he earns good money by doing this, and so he can finance his wife’s education, explains the masculinities researcher.

Male innovation

Øystein Gullvåg Holter calls what is taking place in the Nordic home, an innovation. An innovation that also includes ideology, attitudes and culture. – Welfare has been privatised and individualised, we can’t just depend on the State, and the importance of social innovation and welfare efforts from below have increased. This is what we are seeing in everyday life, and it is especially clear in relation to masculinity. Children and childcare are more important than previously.

One of the Nordic men was asked: “What do you want to be remembered for after your death?” and answered, “I want to be remembered as a good and loving father”. – These men are at their proudest when their children and wife or partner look upon them as a good father. This is the new definition of masculinity. “But what about big, strong and tough?” as was asked in one of the Swedish interviews, to which the man replied: "...and a bit thick in the head, do you mean?” The daddytrack alters masculinity, Holter maintains.

So, perhaps the public debate about men is sometimes a little passe. It builds, perhaps, upon outdated notions about what makes a real man. In the interviews the men are also asked about what is unmanly. – “ To wear make up”, is the reply some give, but the majority don’t have any real answer. They say they prepare meals and clean the house, not just on special occasions but also on a regular basis. And then there are those who say they sew curtains. It’s no longer risky for a man to do this. And I don’t get the impression that their answers have been affected by any demands from their wives. It appears that men’s own demands upon themselves – and also their children – play a more important part than their wives, he says.

The signs of change are evident. Nevertheless, Nordic men and women are characterized by ambivalence, as much of the old thinking on gender is alive and well. – That women choose to stay at home is about them choosing to take responsibility for childcare, but also it is about the family’s career development. This is often a key factor, says Holter. – The man could easily work part-time for a while, the family finances could tolerate it, but this would most probably put him out of the running in the competition for the best jobs. The Swedish masculinities researcher Claes Ekenstram talks of men’s fear of falling, and I believe that many have thought about this. They don’t dare reduce their working hours or take even more responsibility for childcare, because they know that their career opportunities will be reduced.

Icelandic Jump

If the daddytrack is to be realised, then it must also apply to working life. – However, there it hasn’t become established, says Holter. The exception is the father quota in parental leave; One month in Norway and Sweden, three months in Iceland, and now two weeks in Finland. – In Sweden and Norway the father’s quota has existed since the mid-nineties, and is well established , Holter points out. – It’s usually not difficult to obtain leave : “A rule is a rule”, as some of the men interviewed have said. You go to your employer and get the time your are entitled to.

The other Nordic countries are now discussing whether to follow Iceland’s example. They have introduced a three-part parental leave: three months for the mother, three months for the father and three months which the parents can divide between themselves as they wish. In one go they have got three earmarked months. – Debates about the father’s quota have a tendency to become derailed, because there is a tendency to discuss how much the state will decide. However, the men in our interview data don’t experience the father’s quota as coercion or unwanted interference. They look upon it as a balancing out of the real difficulty of combining childcare and work. It makes it okay for the man to take parental leave in spite of career ambitions and often ambiguous cultural signals. They experience it as increasing their options.

– My conclusion is that the Icelandic jump will prove to be more successful than a model with gradual steps. In Iceland they started with a poor scheme for both parents. The broadening of the scheme they have introduced rewards both mothers and fathers. In Norway and Sweden we have had a model where the woman comes first with the father trailing behind. This has led to a debate where giving more to the father means “taking” from the mother, even though there is nothing in the law that states that parental leave is the mother’s. This is about equality! declares Holter.

Inherited pioneer status

Øystein Gullvåg Holter has inherited a pioneer status. His mother was pioneer of Norwegian women’s research, Harriet Holter. – I grew up with a questioning relationship towards gender, says the son. Nevertheless he was not prepared to follow in his mother’s footsteps. Instead, he chose music as a research field. – I criticised those who didn’t think popular music had much to say, because it focused on the heart and on pain. And I became interested in how music is consumed. There’s no getting away from the fact that consumption of popular music is closely tied to starting a new relationship and moving in together, so I wrote about the singles market, Holter explains. The book ”Sjekking: kjærlighet og kjønnsmarked” (“chatting up: love and the singles market”) was published in 1981. In it I describe life in discos, clubs and other chat up locations. – In principle, both partners, women and men, are equal – and free to choose. But the singles market nevertheless reflects inequality and repression, he affirmmed at that time. He now thinks, however, that he went too far by describing women as sex objects who are selected, but they actually choose too. – Additionally, chatting up has become a more equally balanced activity since the 1980s, says the masculinities researcher.

From the singles market it wasn’t a big leap to women’s and gender research. – I was quite a lonely figure there, he says. Not only was Holter jr. a man, but in addition he was interested in men – as a gender. There were many who thought it completely unnecessary, because wasn’t all research in principle about men? It wasn’t however any worse than that he received a doctorate grant from the Norwegian Research Council to research the changing nature of partnerships. – However, instead I “misused” the grant on a three year study of gender and partnership in earlier civilisations and historical research. I learned a great deal from it that later became useful in, among other things, my Doctor of Philosophy thesis. It’s title is “Gender, patriarchy and capitalism: a social forms analysis”.

Male Role Commission

Then came the male role commission. The Swedes were first: Early in the 1980s the Swedish authorities established a work group on the male role. They carried out, among other things, a comprehensive questionnaire survey in order to map out the Swedish man. It caught on. In 1986 the Norwegian government appointed its Male Role Commission, and Holter was given the task of formulating and then interpreting a large research survey. It showed among other things that a third of Norwegian men were positive towards equal opportunities, a third were undecided or neutral and one third were more negative. Eight out of ten were of the opinion that there should be an equal division both outside and inside the home, but only two out of ten actually practised this. The male role commission therefore proposed paternal leave in its concluding report. This was subsequently adopted.

Øystein Gullvåg Holter would take care of the questions, debates and research from the male role commission, even after the final report. The network for research into men was established in 1989. Similar networks were started in Sweden and Denmark. In addition he contributed to an international network in the 1990s that at its height had 3-4000 subscribers to its newsletter. – We ended up with a community of both male and female researchers, who specialised in men and gender, he says.

Goodwill, resistance and Scarce Resources

Ten years later the Norwegian network gave an account of itself and catalogued the following experience: A good deal of sympathy; a good many seminars; and, depending upon how one defines men’s research, between 100 and 200 masters theses, and 5 to 15 Doctoral theses. However, little money; No success in establishing a research program on men, for example. This is probably due to several factors, including competition for scarce resources. – The women had finally succeeded in gaining funding for womens research, so we came forward and cried out, “there is another sex too!”

This did not result in the authorities doubling the funding for gender research. – Instead, we had to share the money that was already available. And this created what was often a difficult situation. Men’s research was met with scepticism. Some people were used to thinking of equal opportunities as a characteristic of women. Or of gender as a purely competitive relationship, where either one or the other must win. In reality, there are incentives for both men and women to maintain patriarchal relationships, Øystein Gullvåg Holter highlights. For example, what type of man does a contemporary woman want? Does she want a breadwinner, a caring man, the tough type, or a softy?

Yes please

Øystein Gullvåg Holter would like to see a new male role. The most important task should be to initiate a more comprehensive debate, focus on the inconsequential and shape a more comprehensive care-oriented daddytrack for men, he says, and not least initiate research. – We should go deeper into processes of innovation that are taking place among men and women; Investigate the variety and diversity that exists; Address the situation of boys and young men and investigate which gender related prejudices they encounter; Look at divorce and men’s health. Additionally, men’s conflict-related behaviour must be addressed, in the opinion of the masculinities researcher. – We have almost taken for granted that an increase in equal opportunities will help to reduce violence. However, the few statistics we have do not gives us a particularly clear answer. And this is something the outside world is really interested in! Norway is seen as having achieved equality, so how has this affected rape and violence, for example? It is important to improve the integration of conflict- and violence-related research with other types of research, for example work-related research and family research. It is possible to ask in ways that are enlightening and that don’t make people into monsters. He says.

This resembles a decree for men’s research and men’s politics. In the opinion of Øystein Gullvåg Holter Nordic politicians should be a little more sober when selling “Nordic gender equality”. – In some areas we have achieved a lot and serve as a model for others. However, I think that most of all this saddles us with great responsibility. It’s not enough to introduce one or two month’s paternal leave. That does not guarantee us an eternal place in the sun. There is one thing I have brought with me from my home: A deep scepticism to assertions that we have achieved equal opportunities. There are so many historical and modern examples that there still remain differences of power and privilege.

Translated by Matthew Whiting, KILDEN.